When delving into the fascinating realm of chemistry, the concept of isomerism presents itself as both intriguing and challenging. Isomers are compounds that share the same molecular formula yet differ structurally, leading to distinct properties. The question arises: which formulas represent compounds that are isomers of each other? To explore this, we will take a systematic approach, dissecting various types of isomers, their characteristics, and some illustrative examples to solidify our understanding.

To embark on our journey, it is essential to first clarify what constitutes an isomer. Isomers can be classified primarily into two categories: structural isomers and stereoisomers. Structural isomers differ in the connectivity of their atoms, while stereoisomers differ in the spatial arrangement of those atoms. Each category further branches out into subtypes, enriching the tapestry of molecular diversity.

Structural isomers can be succinctly categorized into three types: chain isomers, position isomers, and functional group isomers. Chain isomers arise when the carbon skeleton is arranged differently. Imagine two chains of carbon atoms, one a straight line and another branched. They possess the same molecular formula, yet their structural configuration leads to varied physical and chemical properties. For instance, butane (C₄H₁₀) exists as two isomers: n-butane, a straight-chain alkane, and isobutane, which features a branched structure.

Position isomers emerge when the functional group’s position alters within the same molecular framework. Take for example the alkenes of butene. The two isomers, but-1-ene and but-2-ene, both harbor the molecular formula C₄H₈ but introduce variable reactivity and characteristics due to the differing placement of the double bond. This positional variation provides a tangible illustration of how minute changes in molecular structure influence overall behavior.

Functional group isomers represent yet another avenue of isomerism, varying in the type of functional group present despite adhering to the same molecular formula. A classic example is provided by ethanol (C₂H₆O), an alcohol, and dimethyl ether, an ether. Although they maintain the same constituent atoms arranged in the same quantity, their differing functional groups foster contrasting properties and uses, exemplifying the vibrancy of chemical diversity.

Shifting our focus, we turn to stereoisomers, which, as mentioned, maintain identical connectivity but diverge in spatial arrangement. This category is further divided into geometric isomers and optical isomers. Geometric isomers display distinct physical orientations due to the restriction imposed by double bonds or ring structures. The classic case resides in cis-trans isomerism; consider 2-butene again. The cis isomer has both methyl groups on the same side of the double bond, whereas, in the trans configuration, they are oriented across from one another. The disparities in their structural arrangements culminate in differing boiling points and solubility, showcasing the intricate relationship between structure and properties.

Optical isomers, or enantiomers, embody yet another fascinating dimension of isomerism. These are compounds that are non-superimposable mirror images of one another. The presence of a chiral center, typically a carbon atom bonded to four distinct substituents, generates these pairs. A quintessential example involves lactic acid, which possesses two enantiomers: D-lactic acid and L-lactic acid. Although they share the same formula (C₃H₆O₃), their interaction with polarized light and their physiological effects can differ dramatically—a fact that cannot be overlooked in pharmaceutical applications.

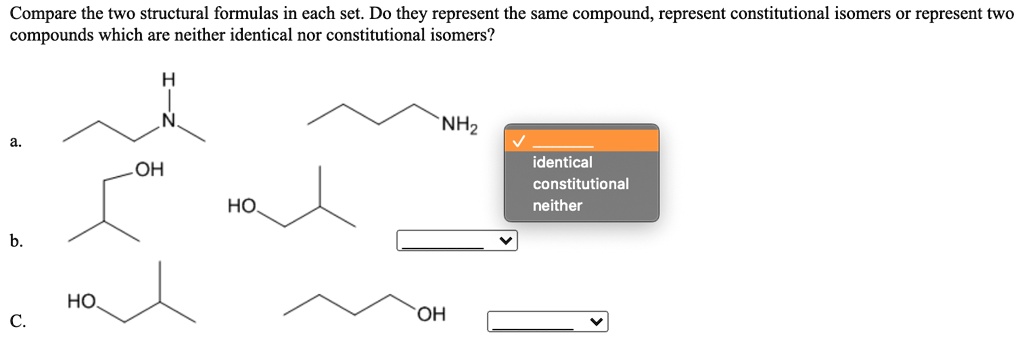

As we traverse the landscape of isomerism, various methods can aid in elucidating the relationship between different compounds. Structural formulas, which clearly illustrate atom connectivity, play a pivotal role. Analyzing these structural representations for patterns delineates which compounds may act as isomers. For individuals embarking on this chemical inquiry, it is advantageous to employ molecular models or software that visualizes three-dimensional configurations. This practice enhances comprehension and retention of isomeric relationships, particularly when tackling more complex organic compounds.

Moreover, there is an underlying challenge: how many isomers can one derive from a given molecular formula? The task often requires meticulous scrutiny, as certain compounds exhibit multiple isomeric forms. For instance, consider pentane (C₅H₁₂), which boasts three structural isomers: n-pentane, isopentane, and neopentane. This encourages not only a theoretical understanding but also practical manipulation in synthetic organic chemistry, propelling the exploration of devised reaction pathways and potential yield efficiency.

In conclusion, the intricate world of isomerism beckons a thorough examination of various formulas and their resultant compounds. By dissecting structural and stereoisomers, one comes to appreciate the profound implications of molecular architecture on properties and reactivity. From the simplest forms to the more convoluted arrangements, each iteration invites inquiry and challenges assumptions about chemical identity. Engaging with the question of isomerism not only enriches our comprehension of chemistry but also opens avenues for innovation and discovery in the scientific pursuit. As you explore the diverse array of isomers, ponder: how does the infinitesimal shift in structure lead to the vast chasm in nature’s behavior? The answers may not only intrigue but inspire future explorations in the field of molecular science.