In the annals of history, few declarations resonate with the same audacity as the phrase, “L’État, c’est moi,” or “I am the state.” This proclamation is attributed to none other than Louis XIV, the Sun King, who ruled France for an astonishing seventy-two years from 1643 to 1715. This statement epitomizes the essence of absolutism and offers insight into the dynamics of power during his reign. However, the assertion raises a tantalizing question: What does it truly mean to equate oneself with the state? In what ways does this expression encapsulate the philosophy of governance and personal authority?

To explore this inquiry, one must first appreciate the historical backdrop against which Louis XIV governed. The seventeenth century was a transformative era in French history, marked by religious wars, feudal strife, and nascent questions about monarchy and governance. In this turbulent context, Louis XIV emerged as a figure determined not only to consolidate power but also to embody the very essence of the French state. Through a series of strategic maneuvers, he sought to diminish the influence of the nobility who had previously challenged royal authority.

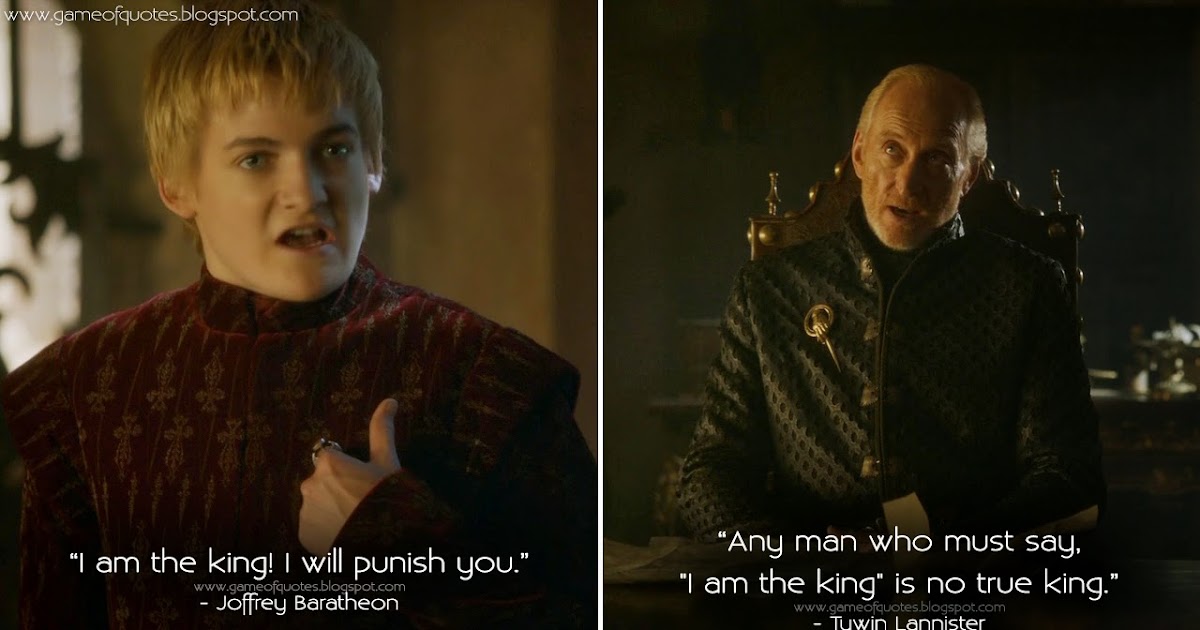

Understanding Louis XIV’s assertion requires delving into the concept of absolutism. Absolutism, as a political doctrine, advocates for the unrestrained authority of the sovereign. Louis XIV’s reign exemplifies this doctrine in its most concentrated form. He famously declared, “I am the state,” symbolizing his belief that the monarchy and the nation were inextricably linked. This convergence of king and country eliminated the notion of shared governance and reinforced the idea that the monarch embodied the will of the people, even as he ruled with an iron fist.

Moreover, Louis XIV’s reign witnessed significant cultural advancements. His patronage of the arts is emblematic of this era. The construction of the Palace of Versailles not only served as a physical manifestation of royal authority, it also became a cultural symbol of France’s grandeur. Versailles was not merely a royal residence; it was a stage for Louis XIV to illustrate his supremacy. By inviting the nobility to reside at Versailles, he effectively curtailed their power while simultaneously elevating the culture of absolute monarchy. Herein lies another question: Can architecture and art serve as extensions of political ideology?

Louis XIV’s self-identification with the state manifests in various facets of governance. He centralized the administration and instituted reforms aimed at streamlining the bureaucracy. By placing loyalists in key positions of power, he ensured that his edicts were executed without interference. This organizational restructuring not only reinforced his control but also allowed for the implementation of policies that would significantly alter French society. Yet, as he centralized power, did he also lay the groundwork for future resistance? The challenge posed by his absolutist rule would eventually catalyze dissent that echoed through the corridors of history.

The legacy of Louis XIV’s reign extends beyond the borders of France. His policies and philosophies influenced the development of modern statecraft and provided a model for subsequent monarchs across Europe. However, his reign also serves as a cautionary tale about the perils of absolute power. The very phrase “I am the state” embodies the duality of kingship: it is a declaration of strength but also a harbinger of vulnerability. As history would reveal, the centralization of power can lead to eventual upheaval, as seen in the French Revolution of 1789, which sought to dismantle the very structures Louis XIV had solidified.

Furthermore, the relationship between Louis XIV and his subjects merits examination. His belief in divine right—a doctrine asserting that monarchs derive authority from God—fueled the notion that he was an indispensable entity in the continuity of the state. Yet, this perspective raises a complex inquiry: How can the interests of a single individual align with the collective needs of the populace? As Louis XIV pursued grand ambitions, like wars of expansion and lavish expenditures, discontent simmered among the populace, unveiling the precarious balance between a ruler’s desires and the reality of the governed.

In contemplating the legacy of Louis XIV and his infamous declaration, it is essential to reflect on the implications of identifying oneself as the state. This assertion is not merely an assertion of authority but also an invitation to critique the nature of leadership itself. What responsibilities accompany such a claim? What accountability exists in a system where the king and the country are perceived as one? These questions resonate with contemporary political discourse, urging us to scrutinize the nature of power, representation, and the citizenry’s role in shaping the state.

Ultimately, the phrase “I am the state” serves as both a statement of absolute power and a profound reflection on the human condition. The challenge amidst Louis XIV’s enduring legacy is to consider the complexities inherent in governance, authority, and the reciprocal relationship between rulers and the ruled. As one reflects upon history, the shadows of past leaders loom large, compelling current and future generations to ponder the timeless question: What does it mean to embody the state, and at what cost?