In the realm of mathematics, specifically within the domain of algebra and functions, understanding the behavior of various functions is pivotal. Among these characteristics, identifying which functions possess precisely one x-intercept and one y-intercept is a fundamental inquiry. This article delves into the essence of intercepts, elucidates the types of functions exhibiting these properties, and presents a coherent framework for comprehending their implications.

Firstly, it is paramount to define the terms “x-intercept” and “y-intercept.” The x-intercept of a function is the point at which the graph of the function intersects the x-axis, denoted as the point ((x, 0)). Conversely, the y-intercept occurs where the graph intersects the y-axis, represented as the point ((0, y)). A function can possess zero, one, or multiple intercepts based on its inherent characteristics and algebraic composition.

Several types of functions are particularly noteworthy in their ability to demonstrate exactly one x-intercept and one y-intercept. The exploration begins with linear functions, which are perhaps the most straightforward and intuitive among them.

Linear Functions

A linear function is characterized by an equation of the form (y = mx + b), where (m) represents the slope, and (b) indicates the y-intercept. The nature of linear functions guarantees that their graphs depict straight lines on the Cartesian plane. For a linear function to exhibit exactly one x-intercept, its slope (m) must be non-zero (i.e., (m neq 0)). This condition ensures the line is not horizontal, which would negate the existence of an x-intercept.

When the slope is non-zero, the graph will invariably cross the x-axis at a single point, thus yielding one distinct x-intercept. Similarly, since all linear functions must cross the y-axis, there will also be precisely one y-intercept where the line intersects the line (x = 0). Consequently, any non-horizontal linear function possesses exactly one x-intercept and one y-intercept, making it a quintessential example.

Quadratic Functions

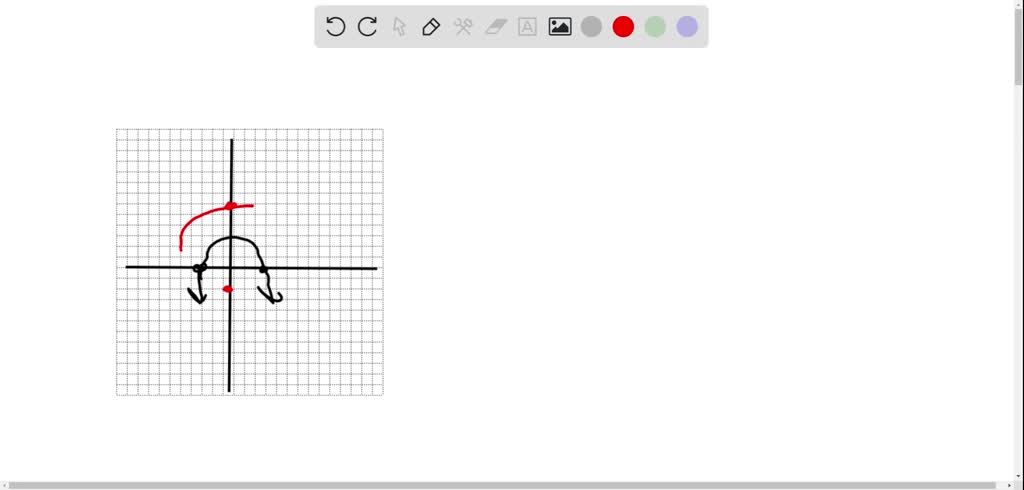

Quadratic functions, represented by the general form (y = ax^2 + bx + c), reveal more complexity. The nature of these functions arises from their parabolic graphs. Depending on the values of (a), (b), and (c), a quadratic function can have zero, one, or two x-intercepts. For a quadratic function to possess exactly one x-intercept, the discriminant, (D), calculated as (b^2 – 4ac), must equal zero. This condition signifies that the parabola is tangent to the x-axis at a single point.

Notably, when a quadratic function has exactly one x-intercept, it will still intersect the y-axis at one point, ((0, c)). Thus, a quadratic function can also meet the criteria of having precisely one x-intercept and one y-intercept under the specific condition that the discriminant equals zero, which results in a unique point of tangency with the x-axis.

Absolute Value Functions

Another intriguing category is that of absolute value functions, represented by equations such as (y = |x – h| + k). Such functions exhibit a V-shaped graph. The configuration of the absolute value function allows for the existence of exactly one x-intercept, contingent upon extending the vertex downward through the x-axis. For these functions, if (k < 0), the vertex lies below the x-axis, ensuring one intersection: the x-intercept.

Similarly, these functions invariably generate one corresponding y-intercept at the vertex’s x-coordinate (h), leading to an intersection point at ((0, |0 – h| + k)). Thus, absolute value functions provide another robust example of functions demonstrating precisely one x-intercept and one y-intercept.

Exponential Functions

Exponential functions such as (y = a^x) (where (a > 0)) can also conform to the criteria of having exactly one x and y intercept, applicable under specific circumstances. The graph of an exponential function approaches the x-axis asymptotically but never quite intercepts it. Only when set in a structure such as (y = a^x + b), where (b) is negative and sufficiently small, can an x-intercept be achieved. This means that there will be one unique point where the function crosses the x-axis, coupled with one y-intercept where (x = 0).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the inquiry into which functions possess exactly one x-intercept and one y-intercept has nuanced answers spread across various function types. Linear functions, certain quadratic functions, absolute value functions, and appropriately defined exponential functions prominently illustrate these characteristics. Each of these functions delineates a distinct yet cohesive functionality on the Cartesian plane, embodying unique mathematical identities while adhering to the requirement of singularity in intercepts. Understanding these nuances enriches one’s comprehension of functional behavior and its implications in broader mathematical contexts.