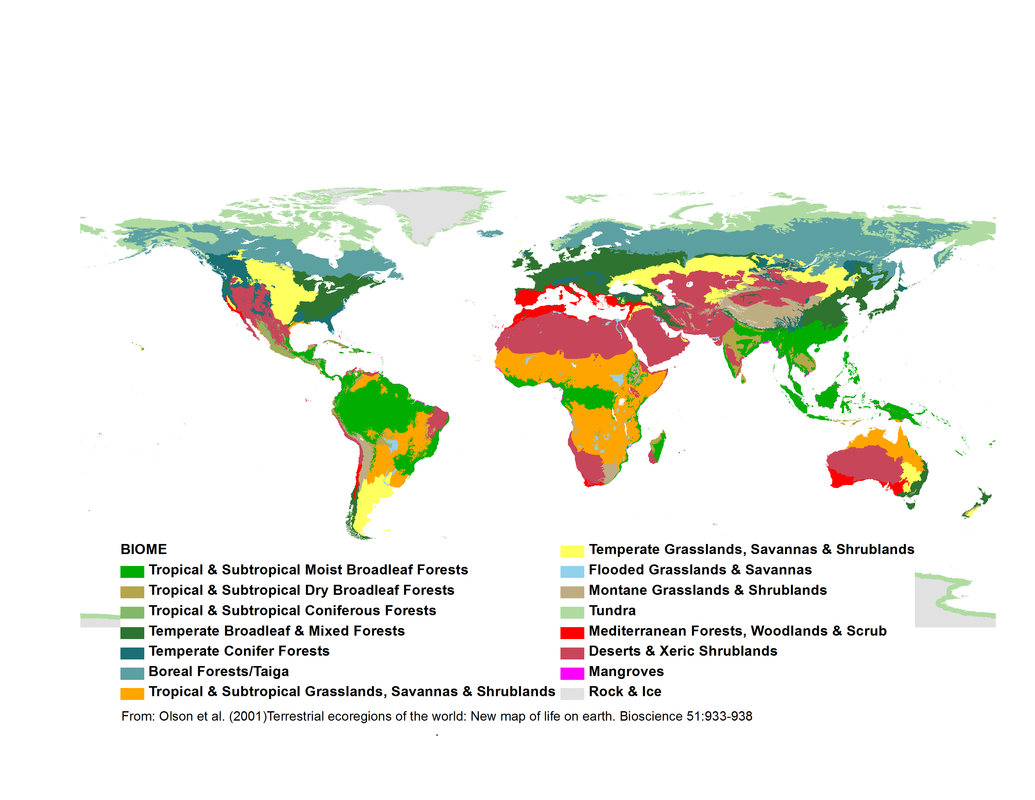

Biomes are vast ecological areas that distinguish themselves through unique climates, flora, and fauna. Each biome contributes to the intricate web of life on Earth, yet not all share the same degree of biodiversity. Understanding which biome has the lowest biodiversity is crucial for appreciating how environmental factors influence species richness and ecosystem stability. This inquiry not only provokes introspection about ecological balance but also compels us to reconsider our relationship with nature.

The biome traditionally identified as having the lowest biodiversity is the tundra. Characterized by extreme cold, a short growing season, and permafrost—permanently frozen subsoil—the tundra presents an inhospitable environment for many life forms. Its harsh climatic conditions drastically limit the types of organisms that can survive, resulting in a relatively sparse and specialized assemblage of species.

Examining the climate of the tundra reveals vital insights into its biodiversity. The harsh winters, with temperatures plummeting to -50 degrees Celsius, deter the proliferation of warm-blooded fauna and diverse plant life. The short summer, albeit sunny, lasts only a few months, permitting a brief window for growth and reproduction. As a result, most tundra plants—such as lichens, mosses, and a few hardy grasses—are low-growing and perennial, emerging only when conditions are favorable.

Biodiversity can be delineated into alpha, beta, and gamma components. In the tundra, alpha diversity—representing the number of species present in a specific area—is minimal. Commonly, only about 1,700 vascular plant species occupy the tundra across its global expanse. This is markedly less than biomes like tropical rainforests, which host approximately 40,000 plant species. The restricted diversity level is reflected in the tundra’s animal inhabitants as well—with a predominant focus on migratory bird species or large herbivores, such as caribou, that are well-adapted to the cold.

Another contributing factor to the low biodiversity in the tundra is the nutrient-poor soil. The accumulation of organic matter is inhibited due to the slow decomposition rates in frigid temperatures. Consequently, nutrient cycling suffers, further limiting plant growth and, in turn, the entire food web. This results in a simplistic ecosystem, where energy transfer is less complex than in more biodiverse environments like forests or grasslands.

When exploring the broader environmental dynamics, it becomes evident that human actions exacerbate the vulnerabilities of tundra biomes. Climate change looms as a formidable threat, primarily due to increased temperatures leading to permafrost thawing. This thawing releases trapped greenhouse gases, further intensifying global warming and altering habitat conditions. Together with other anthropogenic influences—such as oil extraction and industrial development—these factors compound the pressures on an already low-diversity system.

In stark contrast to tundra biomes, diverse ecosystems such as coastal wetlands or temperate forests illustrate the significance of environmental resilience. The intricate interdependencies among various species contribute to stability and recovery following disturbances, like storms or droughts. Biodiversity facilitates this resilience, allowing ecosystems to withstand and adapt to changing conditions. The very fabric of food webs—comprising producers, herbivores, predators, and decomposers—is more robust in these higher-diversity landscapes.

Another astonishing aspect pivots around the evolutionary strategies that organisms in low biodiversity regions exhibit. Survival in the tundra demands remarkable adaptations, including physiological changes—such as antifreeze proteins in Arctic fish or insulating fur in mammals. Such specialized characteristics, while fascinating, result in a narrow niche for the organisms, which relies heavily on specific environmental conditions that may be shifting due to climate fluctuations.

The significance of conservation efforts cannot be overstated. As ecosystems undergo irreversible changes, the existing biodiversity is likely to suffer disproportionately, highlighting the urgency for protecting tundra habitats. Investment in sustainable practices, rigorous research, and creating policies to mitigate climate impact are imperative to safeguard these fragile environments. Failure to act may result not only in direct loss of species but also in the cascading effects on global ecosystems connected to the tundra.

Ultimately, the findings regarding the tundra’s low biodiversity prompt a reevaluation of what constitutes ecological health. The stark realization that this complex biome is seemingly inhospitable to biodiversity challenges preconceived notions about abundance and richness within nature. As we delve deeper into the interconnectedness of life and environment, an understanding of biomes’ specific characteristics takes on profound implications for future conservation practices.

In conclusion, exploring which biome possesses the lowest biodiversity reveals a tapestry of ecological relationships marked by vulnerability. The tundra epitomizes this condition—an area of stark beauty yet fragile existence, burdened by climate change’s dire repercussions. In heightening awareness of these dynamics, we nurture a sense of responsibility toward preserving the delicate balance of our planet’s diverse ecosystems. With gratitude for their existence, we initiate a dialogue that celebrates biodiversity in all its forms, paving the way for informed stewardship of our natural world.