Language is a complex, multifaceted construct, intricately woven into the very fabric of human cognition. The question of how the brain processes and stores known words is a fascinating inquiry that beckons a closer examination of cognitive linguistics and neuropsychology. In understanding which brain structures act as the processors of language, one inevitably delves into the realms of memory systems and their underlying mechanisms. This exploration not only elucidates the workings of language memory but also invites a philosophical contemplation on the nature of understanding itself.

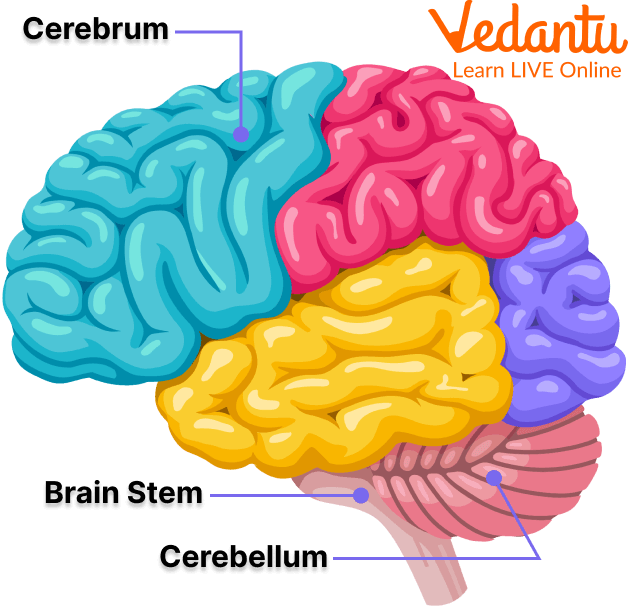

At the heart of language processing lies the concept of language memory, often referred to as the lexicon. The lexicon functions as a mental repository that catalogs the vast array of words, their meanings, and associated grammatical rules. This lexical data is typically stored within an intricate network of neural circuits, primarily located in the left hemisphere of the brain, particularly the temporal and frontal lobes. Yet, the cognitive landscape is not monolithic; rather, it consists of nuanced partitions that specialize in different aspects of language comprehension and production.

The primary players in this cerebral theatre are Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area. Broca’s area, situated in the left frontal lobe, is primarily engaged in speech production and the grammatical structuring of sentences. It orchestrates the fine motor skills necessary for articulation, ensuring that thoughts can be converted into coherent verbal expressions. Disruption to this area can lead to Broca’s aphasia, a condition characterized by halting speech and grammatical errors, albeit with preserved comprehension.

Conversely, Wernicke’s area, nestled in the left temporal lobe, is crucial for language comprehension. It is here that semantic processing occurs; the brain decodes meanings, enabling individuals to derive understanding from spoken or written language. Damage to this area results in Wernicke’s aphasia, wherein individuals produce fluent but nonsensical language, often unaware of their communicative deficits. This bifunctional framework underscores an essential truth: language processing is not merely about the words themselves, but encompasses a dynamic interplay between production and comprehension.

Beyond these two key areas, the angular gyrus and supramarginal gyrus also contribute significantly to language memory. The angular gyrus plays a pivotal role in connecting visual stimuli with auditory information, facilitating reading and writing processes. This intermodality integration allows for a rich tapestry of linguistic experience that is not confined solely to auditory language but extends to visual representations. The supramarginal gyrus, similarly, is implicated in phonological processing, aiding in the conversion of graphemes to phonemes, laying the groundwork for literacy skills.

This neuronal orchestration operates not in isolation but rather in a synchronistic manner. Neuroimaging studies reveal that during language tasks, a network of brain regions engages in concert, coalescing into what is known as the language network. This collective action underscores the cerebral economy with which the brain manages language; it reflects an adaptive design capable of overcoming localized damage through compensatory mechanisms.

As the study of neuroscience and linguistics reveals, language memory is constructed through experience. Each encounter with language—whether through listening, speaking, reading, or writing—induces neuroplastic changes that fortify these neural connections. Synaptic strengthening through repeated exposure creates robust linguistic networks, enabling swift retrieval of words during communication. The idea of ‘sparing’ memory and the dynamic nature of these networks speaks to the brain’s resilience. This adaptability not only promotes efficiency but also means that our lexicon can evolve, accommodating new words and concepts as they emerge.

Moreover, the distinction between explicit and implicit memory provides further insight into how language is retained and utilized. Explicit memory pertains to conscious recollection of facts and experiences, including the ability to articulate the definitions of words and their usage. Implicit memory, on the other hand, encompasses the subconscious knowledge that allows individuals to use language fluidly without engaging in deliberate thought processes. This is evident in the spontaneous production of language during conversation, illustrating a seamless blend of cognitive resources that operate under the radar of conscious awareness.

Looking beyond the structural and functional aspects, the concept of language memory also involves the interplay of social and cultural environments. The socio-cultural context in which an individual is immersed significantly shapes their language acquisition and retention. Concepts such as linguistic relativity suggest that the language we use can influence our thought processes, inherently affecting our capabilities to conceptualize and articulate ideas. Thus, language memory is not merely a biological construct but is also steeped in cultural narratives that dictate meaning and understanding.

As one contemplates the marvels of language memory, it becomes apparent that our brains are not simply hard drives storing information; rather, they are complex, adaptive processors that inform our identity and agency. The intricate workings of Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area, alongside the contributions of supplementary structures, illuminate a paradigm where language is perceived as a living entity, evolving with our experiences and social contexts. This perspective encourages a profound appreciation for the sophistication of human cognition and the remarkable capabilities of our capacity for language.

In conclusion, understanding which brain processor stores known words invites a multifaceted exploration into the architecture of language memory. By unraveling the neural mechanisms that govern our linguistic abilities, we not only unlock the mysteries of communication but also gain insights into the essence of human interaction, thought, and culture. Language, in all its complexity, is a mirror reflecting our experiences, our society, and ultimately, our humanity.