Within the microscopic realm of bone biology, a sophisticated orchestration of cellular entities plays an instrumental role in maintaining the homeostasis and structural integrity of our skeletal framework. Among these myriad cells, osteogenic cells are often heralded as the progenitors of the osseous lineage, giving rise to various specialized cell types essential for bone growth, repair, and remodeling. However, not all cellular denizens of the bone originate from this lineage. To comprehend the multifaceted landscape of bone biology, it is crucial to delve into the cells that emerge from alternative origins. This exploration provides a meticulous examination of those cells that do not derive from osteogenic precursors.

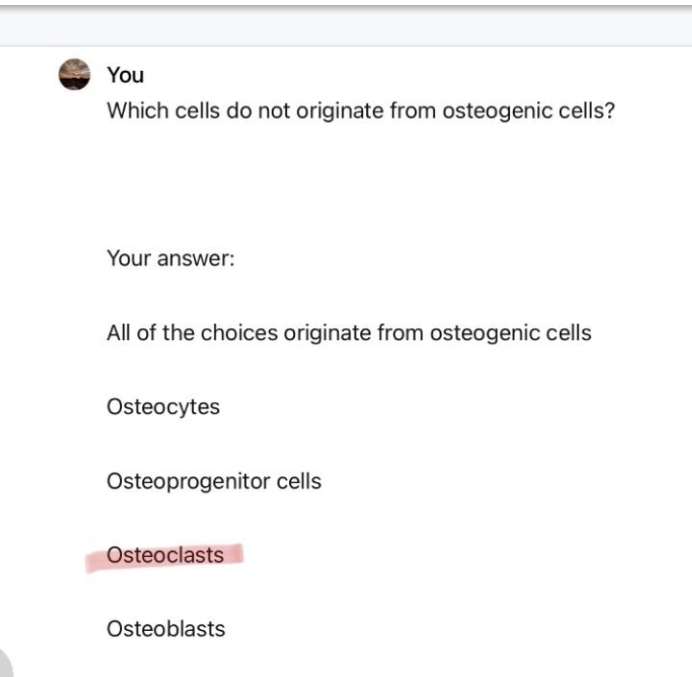

To navigate this intricate tableau, it is prudent first to understand the hierarchy of bone cells. Osteogenic cells, commonly referred to as osteoprogenitor cells, are the primordial architects of bone tissue, residing predominantly in the periosteum and bone marrow. Their primary function is to differentiate into osteoblasts, the cells responsible for bone formation. Yet, lurking beyond the osteogenic lineage are a few notable cell types that contribute significantly to the bone’s structural and functional dynamics, albeit from different existential roads.

One of the most significant cell types that do not stem from osteogenic precursors is the osteoclast. Visualize the osteoclast as a diligent sculptor, tirelessly chiseling away at the existing bone to facilitate the delicate balance of bone remodeling. Unlike the osteoblasts, which build, osteoclasts break down bone tissue. Originating from monocyte/macrophage lineage, these multinucleated giants play an essential role in the resorption of bone, ensuring that the skeletal system adapts to environmental stresses and physiological demands. Through a process known as bone remodeling, osteoclasts reabsorb bone, maintaining homeostasis and enabling the body to respond effectively to the mechanical forces imposed upon it.

Another notable cell type that deviates from the osteogenic path is the chondrocyte. Consider the chondrocyte the silent guardian of cartilage, a critical component of joints and the precursor to endochondral bone formation. Chondrocytes do not develop from osteogenic cells; instead, they arise from mesenchymal stem cells that differentiate into cartilage-forming cells. Their existence is crucial during the early phases of bone development, where they contribute to forming the cartilaginous model that will later ossify into bone. The transformation from chondrocyte to osteoblast signifies a pivotal transition, encapsulating the elegant dance of cellular differentiation that propels bone growth.

In the shadow of these significant cell types lies another category: the adipocytes. These fat-storing cells, which arise from the same mesenchymal precursors as osteogenic cells, occupy an essential niche within the bone marrow. Despite their seeming contradiction to the mineralized grandeur of bone, adipocytes provide both a reservoir of energy and a regulatory function in the hematopoietic environment. The interplay between adipocytes and osteoblasts underscores the complex interdependence of various cell types, revealing a narrative that balances energy storage with structural fortitude.

Moreover, one cannot exclude the contributions of endothelial cells from the conversation surrounding bone biology. These cells populate the interior of blood vessels and are pivotal for the vascularization of bone tissue. Emerging from mesodermal origins, endothelial cells facilitate the transport of nutrients and oxygen necessary for bone health, fostering an environment where osteogenic cells can thrive. A lack of proper blood supply, facilitated by these vital cells, can lead to avascular necrosis, highlighting the importance of their role within the skeletal framework.

As we further investigate the intricate relationships among bone cells, it is also essential to recognize the involvement of the immune system. Cells such as T lymphocytes and osteomacs, a specialized subset of macrophages, also play a role in bone physiology, although they do not derive from osteogenic cells. T lymphocytes can influence osteoclast activity, while osteomacs are involved in the regulation of osteoblast and osteoclast functions, showcasing the harmonious interplay between the immune system and skeletal health.

The dualities present in bone biology, characterized by both constructing and deconstructing cell types, paint a rich tapestry of life. Osteoblasts and osteoclasts embody the yin and yang of skeletal integrity, while chondrocytes facilitate the foundational framework that advances into bone. Adipocytes remind us that beyond rigidity lies a necessity for metabolic balance, and endothelial cells weave a vascular network that nourishes this living tissue.

Understanding which cells do not originate from osteogenic cells offers a panoramic view of bone biology, revealing a narrative filled with intricate relationships and functional interdependencies. The skeletal system is not merely a static structure; it is a dynamic entity, replete with cellular dialogues that ensure its resilience and adaptability in the face of life’s continual demands.

In conclusion, the story of bone biology is one of complexity, where osteogenic cells serve as the architects, yet are supported by a multitude of non-osteogenic cells that are indispensable to maintaining skeletal health. This intricate web of cellular engagement emphasizes the notion that, within the mineralized confines of bone, the interplay of a diverse array of cells fosters a robust and responsive skeletal system.