In the rapidly evolving landscape of network protocols, addressing schemes invariably play a pivotal role in the seamless functionality of the Internet. The transition from IPv4 to IPv6 undoubtedly signifies a monumental shift, characterized by a more expansive address space and enhanced features aimed at alleviating the constraints of its predecessor. Nevertheless, this transformation has fostered a plethora of misconceptions, particularly concerning the various address types supported by IPv6. This article delves into the nuances of IPv6 address types while illuminating the common configuration errors that emerge from misunderstandings in their implementation.

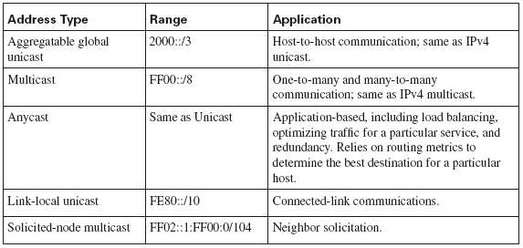

To begin with, it is imperative to understand the fundamental address types that comprise the IPv6 architecture: unicast, multicast, and anycast. Each of these address types serves distinct purposes and adheres to specific operational mechanisms. However, amidst the plethora of capabilities that IPv6 offers, what remains elusive to many network professionals is the intricacies surrounding certain address types that lack support within IPv6.

Unicast addresses, the backbone of IPv6 communications, are utilized to identify a single unique interface on a network. Each device on the Internet is endowed with at least one unicast address, ensuring that data packets reach their intended destination without ambiguity. Conversely, multicast addresses facilitate the simultaneous transmission of data packets to multiple interfaces, thereby streamlining the dissemination of information. Anycast addresses, while akin to unicast in their structure, direct packets to the nearest interface within a group of potential candidates. Together, these address types encapsulate the essence of IPv6 functionality.

However, where does the confusion arise? Many practitioners harbor misconceptions about the potential inclusion of broadcast addresses in IPv6 schemes. Unlike IPv4, which employs broadcast addresses to send information to all devices on a subnet, IPv6 explicitly omits this address type. This deliberate exclusion is pivotal to understanding how IPv6 designs facilitate more efficient and scalable networking. The absence of broadcast mitigates unnecessary traffic, thus optimizing resources and enhancing overall network performance.

One common configuration error arising from this misunderstanding is the inadvertent endeavor to assign broadcast functionality within an IPv6 environment. Network engineers accustomed to the broadcasting paradigm may attempt to replicate this behavior using multicast addresses, erroneously believing that they can achieve equivalent results. This oversight can lead to significant disruptions in data flow and compromise the reliability of the network.

Moreover, confusion surrounding the transition from IPv4 to IPv6 may also give rise to suboptimal configurations. When setting up IPv6, it is critical to ensure that devices are not attempting to communicate through broadcast methodologies. Rather than seeking broadcast solutions, network professionals should embrace alternative strategies such as multicast for group communications. This shift requires a paradigm shift in thinking, urging practitioners to adapt their approach to align with IPv6’s operational framework.

Another aspect worthy of examination is the implications of address types on routing protocols. The adoption of only unicast, multicast, and anycast addresses necessitates a reevaluation of how network routes are established and maintained. Traditional routing algorithms that depend on broadcast communication may falter in an IPv6 ecosystem, leading to unforeseen routing complexities. Understanding the role of address types in the routing landscape is essential for optimizing performance and ensuring robust network operations.

Furthermore, the transition to IPv6 advocates for constancy and consistency in addressing schemes across multitudes of networks. A frequent pitfall occurs when multi-homed networks attempt to utilize overlapping addresses for separate interfaces. Unicast addressing should remain distinct to prevent ambiguity in routing decisions. This requirement underscores the importance of meticulous planning and implementation in IPv6 configurations.

As organizations embark upon the transition to IPv6, fostering an in-depth comprehension of address types becomes paramount. Practitioners must evolve their understanding of network topologies, addressing hierarchies, and the implications of different address types on network performance. IPv6 is not merely an extension of IPv4; it is a foundational reimagining that anticipates future scalability needs and security standards.

In conclusion, acknowledging and addressing the limitations imposed by the lack of broadcast support in IPv6 is crucial for avoiding common configuration errors. With a firm grasp of unicast, multicast, and anycast addresses, network administrators can sidestep the pitfalls of legacy thinking that may jeopardize their network’s integrity. The transition to IPv6 is an opportunity to rethink the conventional paradigms of networking, enabling a more efficient, reliable, and secure future.

By embracing this perspective shift and cultivating a keen awareness of the distinct characteristics of IPv6 address types, professionals in the field of networking can ensure they are equipped to meet the demands of modern networking challenges head-on. The promise of IPv6 lies not only in its vast address space but also in its potential to reshape the way we conceptualize connectivity. It is an invitation to explore new horizons in network architecture and to challenge preconceived notions that may hinder progress in this dynamic field.