The intricate tapestry of human genetics weaves together strands of DNA, whose sequences dictate the phenotypes observed in every individual. Understanding these sequences is vital, particularly in the context of genetic disorders such as Sickle Cell Anemia. This condition is a prevalent example of how a single nucleotide alteration can have far-reaching consequences for human health. By delving into the specifics of the genetic anomaly responsible for Sickle Cell Anemia, one can glean insights into not just this disorder, but the broader implications of genetic mutations.

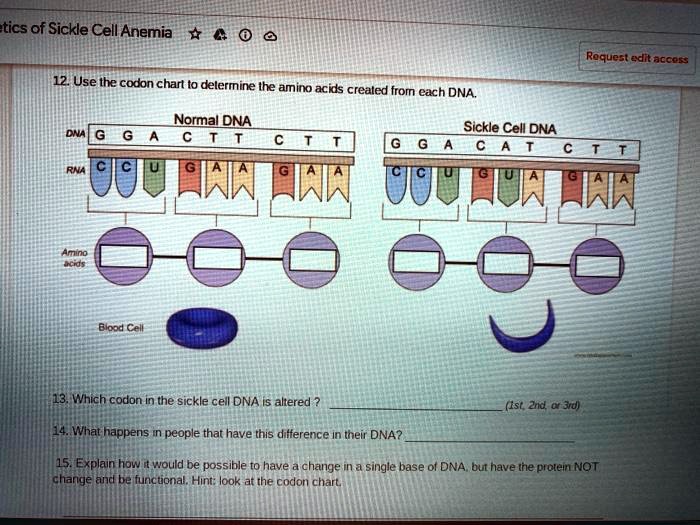

At the heart of Sickle Cell Anemia is a point mutation located in the beta-globin gene, HBB, situated on chromosome 11. This gene is integral to the formation of hemoglobin, the protein responsible for the transport of oxygen throughout the body. The normal version of the hemoglobin beta chain comprises 146 amino acids, where the sequence is typically denoted as GAG (glutamic acid). However, a seemingly innocuous alteration transforms the GAG codon into GTG, leading to the production of valine instead of glutamic acid at the sixth position of the beta-globin chain.

This nucleotide substitution, which may appear trivial, is profound in its consequences. Glutamic acid is hydrophilic, while valine is hydrophobic. The introduction of valine alters the hemoglobin’s properties, leading to the formation of insoluble fibers under low oxygen conditions. This phenomenon precipitates the sickling of red blood cells, which are typically biconcave and flexible. In stark contrast, the sickle-shaped cells exhibit rigidity, causing them to obstruct small blood vessels and lead to a cascade of health complications.

To fully grasp this mutation’s implications, it is essential to consider the biochemical interactions at play. Hemoglobin’s typical function relies on its ability to maintain solubility in oxygen-saturated environments. The aberrant hemoglobin (known as HbS) polymerizes in deoxygenated states, forming crystalline structures that distort the red blood cells. These distorted cells not only impair circulation but also become more susceptible to hemolysis, resulting in anemia—a characteristic symptom of Sickle Cell Anemia.

Furthermore, suffering from Sickle Cell Anemia is not merely a consequence of the altered codon; genetic inheritance plays a pivotal role in the disease’s prevalence. The condition is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. Therefore, an individual must inherit two copies of the mutated gene (one from each parent) to exhibit symptoms. Individuals carrying only one copy are said to be carriers or have sickle cell trait, which often remains asymptomatic but can confer protective advantages against malaria, elucidating the complex interplay of genetics and environmental adaptation.

Examining the mutation through the lens of evolutionary biology reveals the broader implications of genetic mutations. The prevalence of the sickle cell trait is particularly pronounced in populations from malaria-endemic regions. This offers a compelling narrative of natural selection, wherein carriers of the trait experience enhanced survival due to their increased resistance to malaria. Yet, this evolutionary advantage comes with a significant trade-off—the potential for developing Sickle Cell Anemia in the next generation. Thus, this genetic alteration encapsulates a classic dilemma in the study of genetics: the balance between adaptation and disease.

To further unravel the mysteries of Sickle Cell Anemia, researchers have turned to advanced techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. This revolutionary technology holds the promise of rectifying the very mutation that underpins the disease. By specifically targeting the erroneous codon, it becomes conceivable to reverse the mutation, potentially restoring normal hemoglobin function and alleviating the symptoms associated with Sickle Cell Anemia. However, ethical considerations and long-term effects of such interventions remain at the forefront of ongoing debates within the scientific community.

In addition to gene editing, novel therapeutics that modulate the expression of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) are garnering attention. Fetal hemoglobin production tends to suppress the effects of the mutated hemoglobin, mitigating the symptoms of Sickle Cell Anemia. Drugs aimed at stimulating HbF production offer a promising adjunct to traditional treatments, which often include pain management and the prevention of infections.

As the understanding of the genetic underpinnings of Sickle Cell Anemia continues to evolve, so too must our perspectives on genetic health. The remarkable insights gleaned from the study of a single codon alteration serve as a testament to the complexities inherent in our genetic makeup. They challenge us to consider the broader ramifications of genetic mutations—not merely as causes of disease, but as pivotal elements within the grander narrative of human evolution and adaptation.

In conclusion, the codon alteration in Sickle Cell Anemia, characterized by the substitution of glutamic acid for valine, exemplifies the profound impact of minute genetic changes. Such alterations underscore the intricate relationship between genotype and phenotype, paving the way for both scientific discovery and future therapeutic approaches. As research advances, the ongoing exploration of the genetic architecture of Sickle Cell Anemia offers a vivid tableau of the convergence of genetics, medicine, and evolution, encouraging curiosity and deeper understanding of the human condition.