The ancient Maya civilization, known for its remarkable achievements in various domains, offers a wealth of knowledge that has perplexed historians and scholars for centuries. One of the most captivating aspects of their intellectual legacy is the profound understanding of astronomical concepts, particularly the cyclical nature of time, which predated European comprehension. This exploration will delve into the intricacies of Maya astronomy, its implications on their society, and its rediscovery in modern times.

To appreciate the significance of the concept of cyclical time, it is imperative to examine the broader context of how the Maya perceived the cosmos. The Maya initiated their calendrical studies thousands of years ago, developing a complex system that diverged substantially from the linear temporal frameworks prevalent in many contemporary cultures, particularly in Europe during the Renaissance. While European thought was largely entrenched in a linear historical narrative—reflecting a beginning, middle, and end—the Maya embraced a cyclical perspective that emphasized repetition and renewal.

The cornerstone of this cyclical understanding is encapsulated in the Maya calendar system, which includes several interrelated cycles, the most notable being the Tzolk’in (a 260-day sacred calendar) and the Haab’ (a 365-day solar calendar). These two systems interlocked in a 52-year cycle known as the Calendar Round. This intricate calendrical framework not only regulated agricultural activities but also governed religious observances and societal organization. Each day was imbued with specific significance, reflecting a sophisticated comprehension of celestial movements and their correlations with earthly events.

Maya astronomers excelled in observational astronomy, meticulously recording celestial phenomena. They identified patterns in the appearances of Venus, the cycles of the moon, and the movements of other celestial bodies, linking these observations to agricultural timelines and ritualistic ceremonies. For instance, the rising of Venus heralded war or significant events while its setting could indicate periods of peace. This empirical knowledge of the cosmos was fundamental to their survival and cultural identity.

In contrast, during the late medieval period, European scholars were only beginning to challenge the Ptolemaic geocentric model that constrained their understanding of the heavens. The Renaissance marked a significant yet gradual shift towards a heliocentric perspective, championed by figures like Copernicus and Galileo, whose revolutionary ideas would not fully permeate European consciousness for centuries. Therefore, it can be posited that the understanding of cyclical time and its cosmic implications was a profound intellectual achievement of the Maya that lay dormant within the annals of human knowledge until its rediscovery in contemporary times.

This relationship with time allowed the Maya to develop a robust social structure, wherein their calendars dictated not merely the seasons but also the very rhythm of their lives. This cyclical approach fostered a sense of continuity and stability, as individuals recognized themselves as part of a grander cosmic pattern. The reverence for cycles was manifest in their monumental architecture, which often aligned with celestial events, emphasizing their beliefs in divine order and societal harmony.

The Maya’s insights into cyclical time have resurfaced in modern discourse as scholars seek to comprehend the implications of this ancient knowledge. As contemporary society grapples with environmental crises and the consequences of linear progress, the Maya’s cyclical worldview provides a compelling alternative. By recognizing that life is not merely a linear trajectory, but a series of interlocking cycles, new paradigms in sustainability, mental health, and community building emerge.

Moreover, the resurgence of interest in pre-Columbian civilizations prompts a reevaluation of cultural knowledge systems. The ancient Maya’s profound understanding of astronomy is now recognized as a vital contribution not only to regional history but to the broader human narrative. By studying their calendrical systems, we uncover pathways to integrate ancient wisdom with contemporary scientific inquiry, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration that is essential in addressing today’s complex challenges.

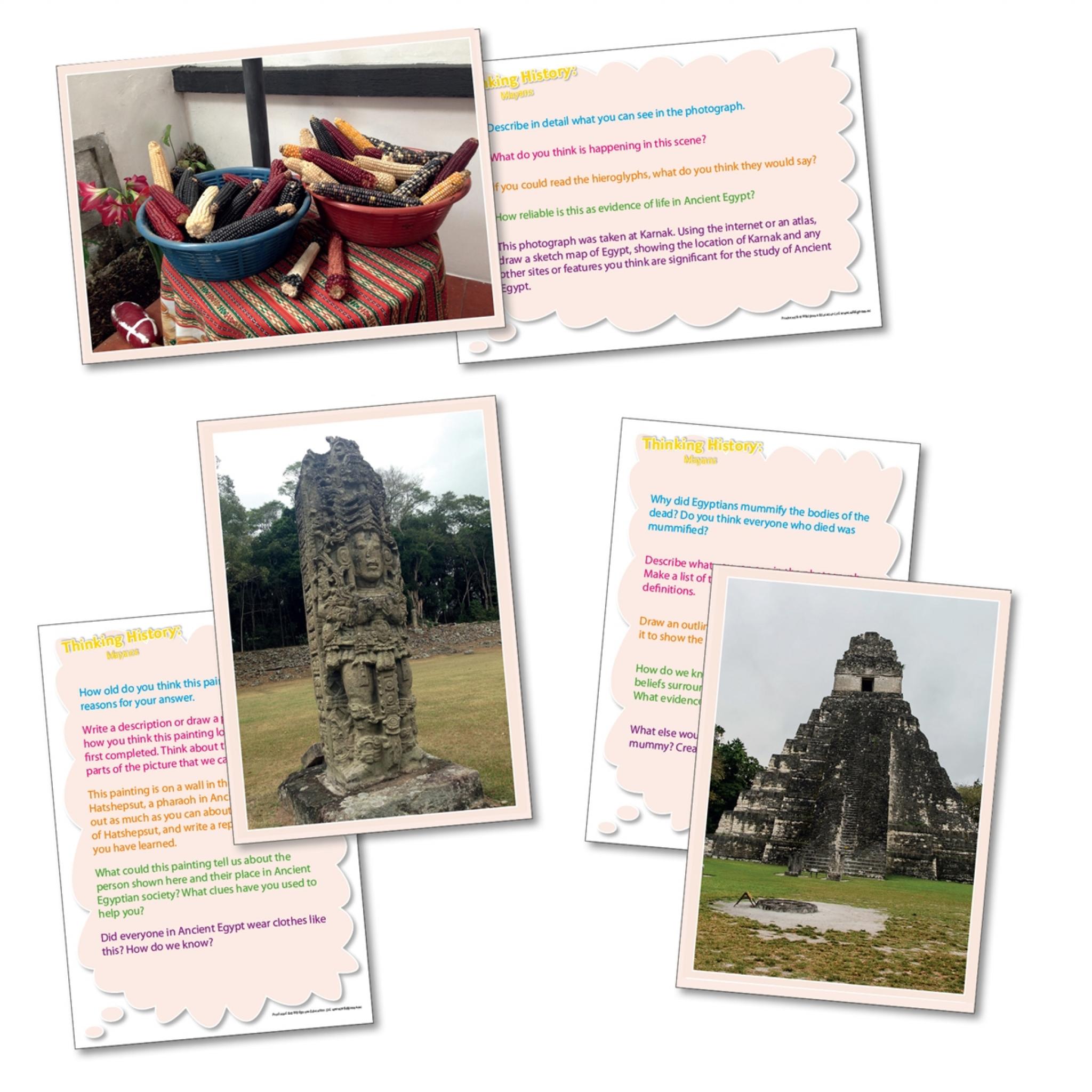

In addition to astronomy, the Maya navigated the realms of mathematics, agriculture, and architecture with a precision that astonished European explorers upon their arrival. The use of a vigesimal (base-20) numerical system and sophisticated calculating methods showcased their intellectual prowess. The construction of pyramids and observatories, especially in cities like Tikal and Chichen Itza, illustrates their keen understanding of both structural engineering and the cosmos. Such accomplishments highlight not merely an awareness of the natural world but an intimate connection to it—an ideology that remains remarkably relevant as we confront the ecological ramifications of our actions.

Conclusively, the concept of cyclical time is but a fragment of the broader intellectual tapestry woven by the Maya. Their understanding of the cosmos and its rhythmic patterns not only set them apart from their contemporaries but also serves as an enduring source of inspiration and insight for our current era. As history continues to unfold, the ancient knowledge rediscovered embodies the potential for a richer, more integrated approach to understanding our place within the universe. The Maya stand as a testament to the timeless nature of human inquiry and the profound connections that transcend temporal boundaries, urging contemporary societies to embrace such wisdom in pursuit of harmony with the world around them.