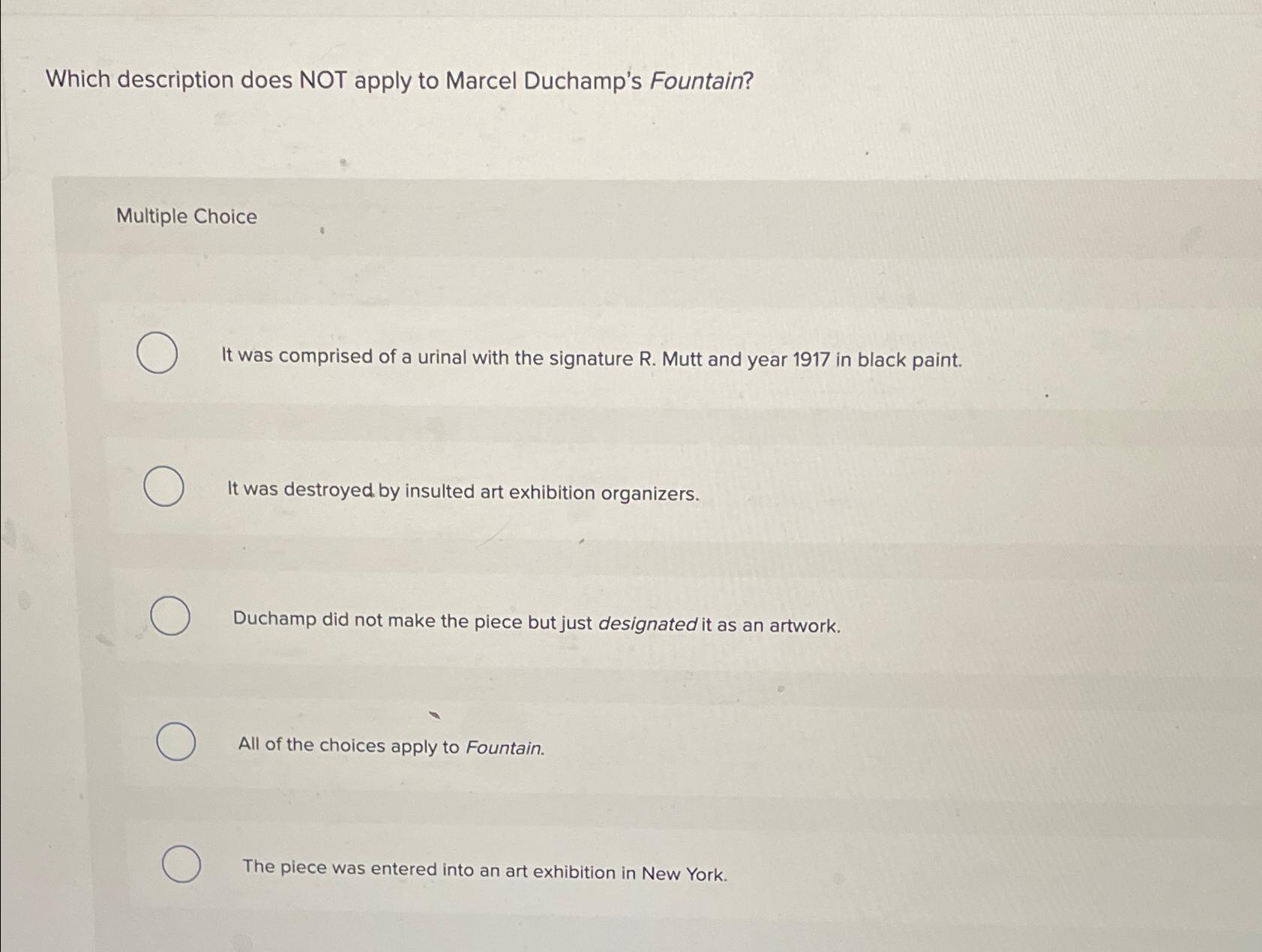

Marcel Duchamp’s *Fountain* stands as one of the most significant and enigmatic artworks in the pantheon of modern art. This piece, which is nothing more than a urinal turned on its side, has provoked a multitude of interpretations and re-evaluations of what constitutes art. Yet, in the journey to understand Duchamp’s intentions and the implications of this work, a compelling inquiry arises: Which description does not apply to Duchamp’s *Fountain*? To traverse this question, one must delve into the connotations surrounding this audacious piece, examining prevalent critiques and erroneously attributed descriptions.

Firstly, it is imperative to consider *Fountain* within the context of its historical milieu. Artworks traditionally embody notions of beauty, craftsmanship, and subjectivity. Duchamp subverted these conventions by presenting a mass-produced object, thereby challenging the very essence of artistic value and originality. The description of *Fountain* as a mere vandalistic gesture, however, belies its substantial philosophical weight. It is not a simple act of destruction but rather an intelligent commentary on the commercialization of art, encapsulating the dissonance between mass production and individual creativity.

Secondly, while many regard *Fountain* as a symbol of anti-art, categorizing it as representing nihilism misses Duchamp’s nuanced intentions. Nihilism suggests a total rejection of values, yet Duchamp’s work implores viewers to reassess their predetermined judgments about aesthetics and artistic intent. It invites an intellectual engagement rather than a mere dismissive critique. To assert that *Fountain* embodies absolute nihilism disregards the dialogue it inspires on conceptualism, value, and the legitimacy of art in socio-political realms.

Moreover, labeling *Fountain* as an avant-garde masterpiece implies a definitive, bounded identity, one that circumvents its potential for broader interpretations. Duchamp developed *Fountain* as part of his larger oeuvre, but it simultaneously exists in a state of flux, forever open to new interpretations. By containing the piece within strict categorization, one fails to recognize its expansive capacity to engage with diverse contemporary dialogues regarding identity, gender, and consumerism.

A frequently overlooked aspect of *Fountain* is its relationship to humor and irony. While some texts emphasize its serious implications, positioning it as a sober critique of the art world, such a description neglects Duchamp’s playful nature. He embraced absurdity, suggesting that fun and levity can coexist within profound philosophical inquiry. Taking *Fountain* too earnestly, then, flattens its multiple dimensions, stripping it of the rich layers of wit that characterize much of Duchamp’s work.

In addition, the notion of *Fountain* as an example of “ready-made” art can lead to misunderstandings about its conceptualization. Duchamp did not invent the idea of utilizing found objects; however, he revolutionized the context in which these objects could be perceived. To proclaim that *Fountain* merely exemplifies a “ready-made” reduces its stature to a technique rather than a profound philosophical stance on the nature of art. Duchamp selected the urinal not merely for its physical attributes but for the discussions it incites regarding authorship, context, and interpretation. Hence, describing it solely through the lens of ready-mades oversimplifies the complexities inherent in the work.

Moreover, *Fountain* is frequently misconceived as an inconsequential contribution to art history. This assertion arises from perceptions that it lacks aesthetic refinement, relying purely on its conceptual framework for merit. Yet Duchamp’s work is far from inconsequential; it reverberated through subsequent movements such as Dadaism, Surrealism, and Pop Art. The impact of *Fountain* extends into postmodern discourse, challenging essentialist views of artistic value and fostering an ongoing reevaluation of art’s role in society.

Yet, to consider *Fountain* as solely cynical reduces its rich engagement with societal norms. Duchamp’s playful antics were significant in the historical progression of avant-garde art, yet to ascribe cynicism as a primary trait undermines the importance of joy and discovery that permeate his body of work. Challenging established norms for the sake of beauty or humor invites a rediscovery of life’s paradoxes rather than a mere embrace of disillusionment.

Ultimately, addressing which descriptions do not apply to *Fountain* reveals much about the evolving discourse surrounding modern art. The piece remains a locus of fascination due to its multifaceted nature, challenging traditional philosophies while demanding a re-examination of foundational art theories. Rather than viewing *Fountain* through a reductive lens, one must recognize the vibrant tapestry of discussions it fosters. Duchamp’s radical choices continue to spark debate, maintaining relevance even in contemporary artistic dialogues.

In conclusion, the inquiry into Duchamp’s *Fountain* extends far beyond a series of negations. Each errant description serves to illuminate the complex layers of meaning interwoven within this provocative artwork. Rather than dismissing *Fountain* based on selective interpretations, one should engage with it as an evolving dialogue, a reflection of societal mores, and a testament to the timeless capacity of art to challenge and inspire. Duchamp’s work illustrates that to gaze upon an object is not merely to see, but to reflect, to ponder, and ultimately, to understand the profound implications of what art is and can be.