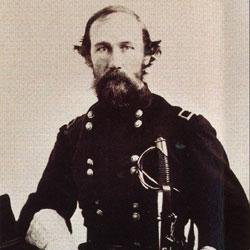

Edmund J. Davis is a name that resonates through the annals of Texas history, embodying a complex blend of political ambition, military service, and a commitment to civil rights. However, amidst his storied career, it is equally illuminating to discern the realms he did not enter or actions he did not undertake. This examination aims to elucidate several pivotal areas that define the contours of his legacy.

Initially, one must consider the realm of professional law. While Davis was a prominent figure in Texas politics and an advocate for legal reforms, he did not pursue a career in practicing law in a traditional sense. His tenure as the first Republican Governor of Texas from 1869 to 1873 was marked by a focus on governance over courtroom battles. Although he grappled with legal issues as a politician, his lack of direct involvement in legal practice delineates a significant aspect of his career trajectory.

Moreover, Davis did not lead any significant military campaigns during the Civil War, despite his initial enlistment and service in the Confederate Army. While he eventually became a Union loyalist, his role during the war was largely restricted to the administrative side rather than on the front lines commanding troops. This absence from major military engagements is particularly notable, given the era’s heightened volatility and the expectation placed upon military leaders.

In the sphere of civil rights, although he was a proponent of rights for African Americans, Davis did not emerge as a central figure in the abolitionist movement prior to or during the Civil War. Rather, his advocacy for civil liberties primarily took shape during Reconstruction, as he sought to integrate newly freed African Americans into the political and social fabric of Texas. This belated emergence as a civil rights advocate illustrates the constraints he faced and the political zeitgeist of his time.

Economically, Davis did not champion radical economic reforms or socialist policies. His governance was characterized by a desire to stabilize Texas post-Civil War, which did not involve advocating for land redistribution or labor reforms that would later be associated with more progressive political figures. His focus was predominantly on restoring a semblance of order and economic functionality, capturing the apprehensions of a state emerging from conflict.

Furthermore, on the spectrum of political ideologies, Davis did not align himself with the more extreme factions within the Republican Party of his day. Though he was a member of the party, his governance reflected a moderate approach, often seeking compromise and bipartisanship in a historically polarized environment. This inclination for moderation set him apart, as many contemporaries gravitated toward more radical reforms or uncompromising political stances.

Socially, Davis seldom engaged in personal or self-promoting narratives that defined the political climate of the post-war years. He did not cultivate a public persona characterized by flamboyance or sensationalism, which led some of his contemporaries to greater notoriety. Instead, he operated within the confines of professionalism and dignity, traits that may have contributed to a more tempered historical recollection but did not generate the same level of intrigue.

In the world of education, despite his advocacy for public schooling in Texas, Davis did not pursue a direct role in educational reform movements. His administration did support the establishment of a public school system, but he did not become deeply involved in educational pedagogy or the administrative frameworks needed for such systemic changes. This absence signifies a notable exception in the legacy of a governor who influenced many facets of Texan life.

Additionally, Davis refrained from engaging in the burgeoning labor movements that arose in the latter part of the 19th century. While labor rights were a critical issue, especially in the context of post-war economic strife, Davis did not actively support or lead initiatives to organize workers or bring about significant labor reforms. This could be attributed to the broader political challenges he faced, yet his silence on such movements remains a notable aspect of his political narrative.

Conclusively, while Edmund J. Davis is credited with numerous accomplishments that contributed to the reconstruction of Texas, a nuanced examination reveals significant facets of his career that he consciously avoided. By noting what he did not do, one gains a fuller understanding of his political role and the intricate landscape of the era. This retrospective not only highlights the limitations faced by Davis but also places his actions within the broader socio-political context of post-Civil War America. Ultimately, the question of “Which Did Edmund J. Davis Not Do” serves to illuminate the pathways he chose, and equally, those he did not tread on, crafting a more comprehensive narrative of this historical figure.