Understanding the intricacies of atomic properties can often feel like navigating a complex labyrinth. Among the plethora of characteristics that define an atom, electronegativity stands out, influencing how atoms interact within molecules. But have you ever pondered which atoms exhibit the lowest electronegativity? This inquiry not only fuels academic curiosity but also encourages a deeper engagement with the subject of chemistry. As we delve into the periodic table and explore this concept, prepare to encounter a fascinating landscape where unique atomic behaviors unfold.

To effectively traverse this discussion, we shall first delineate what electronegativity actually means. Electronegativity is a measure of an atom’s propensity to attract electrons within a chemical bond. This property varies significantly across the periodic table, shaped largely by an atom’s atomic number and the distance of its valence electrons from the nucleus. Consequently, a nuanced understanding of electronegativity necessitates a comprehensive review of periodic trends.

The periodic table, with its meticulously arranged elements, serves as a geographical map for these trends. As we journey from left to right across a period, a salient observation is the increase in electronegativity. This phenomenon is attributable to the rising nuclear charge, which exerts a stronger attractive force on the electrons. Conversely, as we traverse down a group, electronegativity typically diminishes. This decline is due to the increased distance between the nucleus and the valence electrons, resulting in a weaker pull. Thus, as we engage with the periodic table, we are equipped with the foundational knowledge needed to identify those elements with the lowest electronegativity.

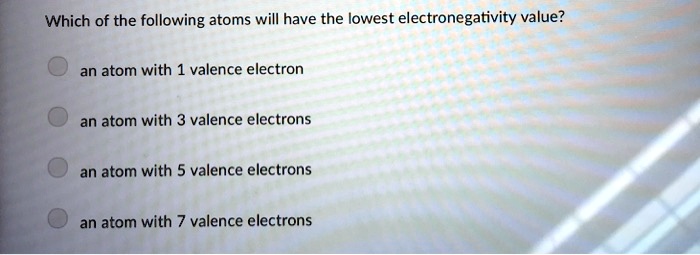

Next, let us turn our attention to the candidates vying for the title of lowest electronegativity on the periodic table. It comes as no surprise that we find the alkali metals—those elemental darlings residing in Group 1—occupying this coveted position. Particularly, cesium (Cs) and francium (Fr) emerge as the most electronegative deficient contenders, with electronegativity values of 0.79 and 0.7 on the Pauling scale, respectively.

But what propels these atoms to possess such low electronegativity? The answer lies in their atomic structure. Alkali metals possess a singular electron in their outermost electron shell, which they are keen to relinquish in order to achieve a more stable electron configuration resembling that of noble gases. This pronounced inclination to lose an electron diminishes their desire to attract additional electrons, thereby contributing to their low electronegativity scores.

Furthermore, let us consider the implications of low electronegativity in chemical bonding. Atoms characterized by such properties are typically less capable of forming covalent bonds that involve shared electron pairs. Rather, they tend toward ionic bonding, where electrons are transferred rather than shared. For example, when cesium reacts with chlorine, it donates its outermost electron to the chlorine atom, resulting in the formation of ions that subsequently attract each other due to electrostatic forces. Such examples illuminate how the low electronegativity of certain atoms pivots their interactions and compound formations.

As we explore the ramifications of low electronegativity, the role of other elements must not be dismissed. While alkali metals reign supreme in this category, it is prudent to also consider other elements with relatively low electronegativities. For instance, certain alkaline earth metals, including barium (Ba) and radium (Ra), also exhibit low attraction for electrons, albeit slightly higher than their alkali metal counterparts. Their propensity to lose electrons reflects a commonality with alkali metals, albeit with a distinct positioning within the periodic table.

This notion raises an intriguing question: Could low electronegativity correlate with metallic properties? Generally speaking, atoms with low electronegativity are found among metals, which are notorious for their malleability, conductivity, and luster. Therefore, the examination of electronegativity not only enriches our comprehension of atomic behavior but also interlinks with the broader narrative of metallic characteristics.

In summation, understanding which atoms possess the lowest electronegativity introduces us to a world where atomic structures govern chemical interactions. Alkali metals emerge as the primary contenders for this title, specifically cesium and francium, distinguished by their electron-losing tendencies that lead to minimal electron attraction. Additionally, the exploration expands to neighboring elements and the broader implications of low electronegativity in bonding, metallic properties, and chemical reactivity.

As we conclude our periodic table excursion, we invite further reflection: How might the characteristics of low electronegativity inform advancements in material science or chemical syntheses? The answers may lie within the very atoms that captivate our scientific imaginations. Delving into the nuances of electronegativity reveals an intricate relationship between atomic behavior and chemical bonding—one that continues to inspire research and exploration in chemistry.