The human body is a marvel of biological engineering, comprised of an intricate web of systems that enable movement, sensation, and, importantly, healing. Understanding the nuances of healing—specifically, which body parts take the longest to mend—offers profound insights into our anatomy, physiology, and the factors influencing recovery. This exploration not only illuminates the physiological processes involved but also challenges common perceptions about the body’s resilience and repair mechanisms. Let us delve into the intricate tapestry of human recovery, shedding light on the factors that contribute to prolonged healing times for specific body parts.

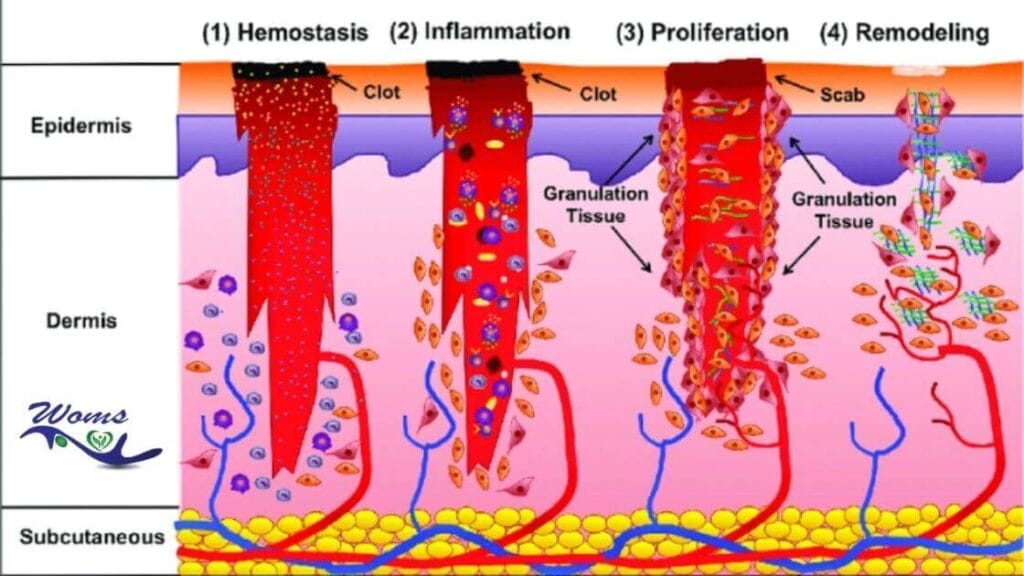

When discussing the human body’s ability to heal, it’s crucial to appreciate the complexity of various tissues involved. Healing encompasses a series of biological processes, including inflammation, tissue regeneration, and remodeling. Each body part possesses unique attributes and challenges that significantly affect healing duration. Not all injuries or conditions recover uniformly, and numerous variables—such as blood supply, tissue type, and age—contribute to this variability.

One of the most infamous slow healers in the human anatomy is the cartilage. Found in joints, ears, and nose, cartilage is avascular, meaning it has no direct blood supply. This characteristic complicates its recovery process after injury. When cartilage suffers a tear or damage, the body has a limited capacity to supply the needed nutrients and healing agents. Consequently, individuals with cartilage injuries often face extended rehabilitation periods, sometimes leading to chronic joint pain.

Moreover, the spinal discs, which serve as shock absorbers between the vertebrae, embody another composite of slow healing. As individuals age, these discs experience depredation and become more susceptible to injury. The limited blood supply, akin to that in cartilage, results in a protracted recovery period post-injury. Damage to the spinal discs can lead to debilitating conditions such as herniated discs, which not only require extensive healing time but often necessitate surgical intervention. Herein lies the juxtaposition of the body’s incredible adaptability and the inherent limitations imposed by its structure.

Equally noteworthy is the healing process of bone tissue. While it is generally known that bones can regain strength after fractures, the timeline for true healing can be surprisingly lengthy, particularly for larger bones such as the femur. Healing a broken bone comprises several phases: inflammation, callus formation, and bone remodeling—all of which can be influenced by age, nutritional status, and external factors, such as stress on the injury site. Younger individuals typically experience speedier healing due to robust blood flow and metabolism. In contrast, older adults may require months for complete recovery, often exacerbated by conditions such as osteoporosis, which impedes the remodeling process.

The healing of soft tissues, including muscles and tendons, emerges as another complex labyrinth. Muscle injuries, often the result of acute trauma or overuse, exhibit varying recovery times based on the severity of the tear, the extent of damage, and the targeted rehabilitation regimen. Grade I strains might resolve in a matter of weeks, while Grade III tears may take several months or longer to heal completely. Tendons, on the other hand, are particularly notorious for prolonged recovery times due to their limited vascularity and the high tensile strength required for functional restoration. This is notably evident in the Achilles tendon, where reinjury rates are high due to the propensity for overly ambitious rehabilitation efforts.

Furthermore, chronic wounds offer a unique perspective on healing complexities. Conditions such as diabetic foot ulcers exhibit an ability to resist recovery, often leading to severe complications. These wounds, prevalent particularly among individuals with compromised circulatory systems, can amplify healing time to several months, highlighting the interplay between systemic health and localized healing processes.

Psychological factors also play a critical role in healing duration, introducing the dimension of mind-body interaction. Stress, anxiety, and depression can significantly hinder the body’s natural healing response. The intricate link between emotional well-being and physical recovery underscores the necessity for a holistic approach to healing, especially for conditions with drawn-out recovery timelines. Exercises such as mindfulness, meditation, and stress management can complement conventional treatments, fostering more conducive recovery environments.

To encapsulate, the body parts that typically take the longest to heal include cartilage, spinal discs, bone tissues, muscles, tendons, and chronic wounds. Each category presents a unique set of challenges and recovery dynamics, influenced by a multitude of factors including vascularity, tissue type, age, and psychological state. Recognizing these variances fosters a deeper appreciation of the intricate processes underpinning human bodily recovery.

This journey through the realm of healing not only clarifies the complexities involved but also encourages a shift in perspective regarding our understanding of the human body’s limits and potential. Knowledge empowers, and as we grasp these intricacies, we can approach healing with patience, optimism, and a comprehensive strategy that considers all facets of recovery. The road to healing may be protracted, but the body, resilient as ever, continues to strive towards restoration and balance.