Bone formation is a fascinating biological process, intricately tied to the overall architecture of the human skeletal system. Among the various processes that give rise to bone tissue, intramembranous ossification stands out as a significant mechanism responsible for the formation of certain types of bones. However, it is crucial to understand that not all bones in the human body arise from this particular type of ossification. This article elucidates the distinction between the bones formed through intramembranous ossification and those that are not, while also exploring the rich tapestry of bone formation processes.

Intramembranous ossification primarily involves the direct transformation of mesenchymal tissue into bone. This process is characterized by the condensation of mesenchymal cells, which then differentiate into osteoblasts, the cells responsible for bone formation. The bones primarily formed through this method include the flat bones of the skull, the clavicle, and certain facial bones. These bones are typically characterized by their broad, flat shapes and are crucial for protecting the brain and facilitating craniofacial structure.

In stark contrast, endochondral ossification is the alternative process of bone formation, wherein a cartilaginous model is gradually replaced by bone tissue. This is a more complex process that involves the development of hyaline cartilage, which serves as a template for subsequent ossification. Long bones, such as the femur, tibia, and humerus, along with the vertebrae, develop through this mechanism. The significance of understanding which bones undergo each process highlights the diversity in the skeletal system’s development.

The primary question at hand is: which bone is not formed by intramembranous ossification? A prime example is the long bones, including the femur—arguably one of the largest and most critical bones in the human body. The femur, with its elongated structure, is a quintessential representation of bones formed through endochondral ossification rather than the intramembranous pathway.

Understanding the differences between these two types of ossification not only sheds light on the development of various bones but also emphasizes the evolutionary adaptations of the skeletal system. The ability to grow and remodel bone is vital for maintaining structural integrity, supporting movement, and protecting vital organs. This adaptability allows the skeleton to respond to various factors, ranging from mechanical stress to hormonal changes with age.

Diving deeper, the general process of intramembranous ossification begins with mesenchymal stem cells that cluster and differentiate into osteoprogenitor cells. These then mature into osteoblasts, which secrete osteoid, an organic matrix that serves as a scaffold for mineral deposition. As the osteoid is mineralized, the formation of woven bone occurs—an initial stage that later matures into lamellar bone, providing enhanced structural stability and strength.

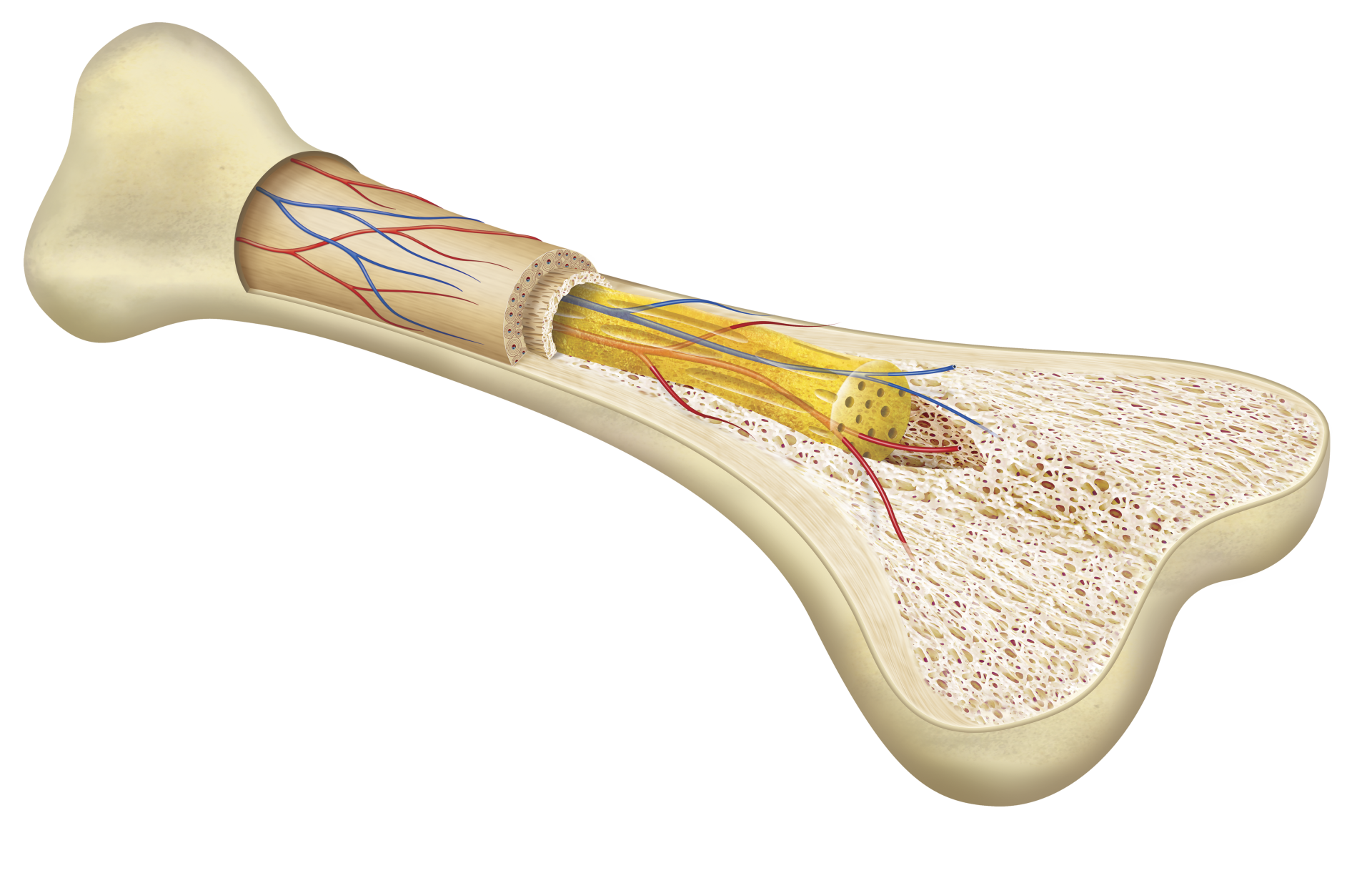

On the other hand, endochondral ossification follows a more gradual timeline. Initially, a hyaline cartilage model is established, and chondrocytes proliferate, contributing to the elongation of the model. As development progresses, the cartilage matrix calcifies, forming a permeable structure that is gradually invaded by blood vessels and osteoblasts. Concurrently, osteoclasts resorb portions of the dying cartilage, making way for the expansion and mineralization of bony tissue. This transition reflects a dynamic interplay between different cell types, highlighting the complexity of the skeletal development process.

Furthermore, it is intriguing to assess how these different ossification processes are regulated. Numerous growth factors and signaling molecules play pivotal roles in orchestrating bone development. For instance, the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling pathway has been implicated in promoting endochondral ossification, while bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are crucial for initiating intramembranous ossification. This regulatory nuance underscores the delicate balance governing skeletal growth and the profound implications when these processes are disrupted, leading to conditions such as dwarfism or skeletal deformities.

In conclusion, the dichotomy between bones formed via intramembranous versus endochondral ossification illustrates a remarkable aspect of human anatomy. The femur stands as a representative example of bones that emerge from endochondral ossification, distinctively contrasting with the flat bones that form through the former. Grasping these concepts not only enriches our understanding of bone biology but also encourages continued exploration into the intricacies of skeletal development and its myriad influences on health and disease. As we uncover the complexities of bone formation, we gain insights that hold potential for therapeutic innovations in treating skeletal-related ailments, ultimately enhancing our understanding of human biology itself.