In the vast and intricate world of biology, the study of cell structures and their respective functions is a fundamental endeavor, providing vital insight into the mechanisms of life. Each cell, often regarded as the basic unit of life, is a miniature universe bustling with specialized structures, known as organelles, that fulfill a specific set of roles. This article will explore key cellular organelles, match each with their primary functions, and illuminate the fascinating interplay between structure and function within biological systems.

The Nucleus: Control Center of the Cell

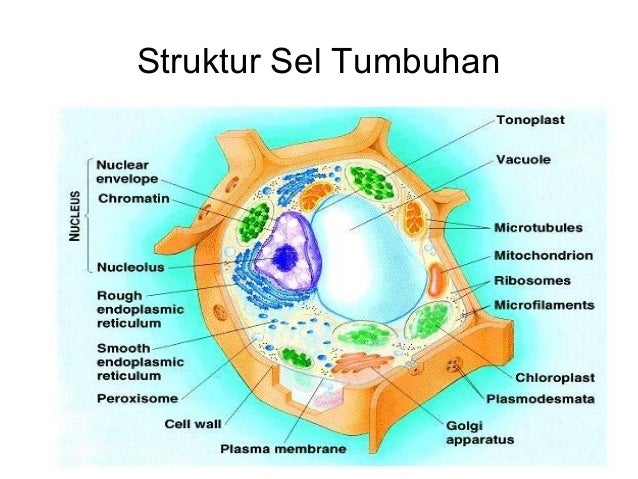

One of the most prominent organelles within eukaryotic cells is undoubtedly the nucleus. Enveloped in a double membrane known as the nuclear envelope, the nucleus houses the cell’s genetic material. It orchestrates cellular activities by regulating gene expression and facilitating the synthesis of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) in the nucleolus. The nucleus serves as the control center, dictating everything from growth to metabolism and the intricate processes of cell division. Its role is essential in maintaining the integrity of genetic information across generations.

Mitochondria: The Powerhouses

Mitochondria, often referred to as the powerhouses of the cell, are double-membrane-bound organelles that generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy currency of the cell. By utilizing oxygen and glucose through the process of aerobic respiration, mitochondria convert chemical energy stored in nutrients into a form that cellular processes can readily utilize. The presence of their own unique DNA suggests a fascinating evolutionary history, tracing back to free-living prokaryotes that formed a symbiotic relationship with ancestral eukaryotic cells.

Ribosomes: The Protein Factories

Ribosomes, the cellular machineries responsible for protein synthesis, can either float freely within the cytoplasm or be bound to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). These minute structures translate messenger RNA (mRNA) sequences into polypeptide chains, thereby facilitating the construction of proteins essential for cellular structure and function. The universality of ribosomes across all forms of life underscores their crucial role in the fundamental processes of biology, serving as the nexus where genetic information is transformed into functional products.

Endoplasmic Reticulum: The Intricate Network

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) exists in two forms: rough (RER) and smooth (SER). The rough ER, studded with ribosomes, plays a crucial role in the synthesis of proteins destined for secretion or for use in the cell membrane. In contrast, the smooth ER is involved in lipid synthesis, detoxification, and the metabolism of carbohydrates. The extensive network of the ER is reminiscent of a factory assembly line, efficiently coordinating numerous cellular processes and ensuring proper product assembly and distribution.

Golgi Apparatus: The Cellular Post Office

The Golgi apparatus functions as the cell’s post office, modifying, sorting, and packaging proteins and lipids synthesized in the ER for secretion or delivery to other organelles. Through a series of membrane-bound vesicles, the Golgi apparatus ensures that molecular cargo arrives at its intended destination accurately. This organelle’s ability to facilitate cellular communication and transport is vital for maintaining cellular organization and responsiveness to environmental stimuli.

Lysosomes: The Digestive Enzymes

Lysosomes are membrane-enclosed organelles that contain hydrolytic enzymes responsible for degrading macromolecules, including proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates, and lipids. Often referred to as the cell’s waste disposal system, lysosomes play a crucial role in autophagy, the process whereby obsolete cellular components are recycled. Their function is essential for cellular homeostasis, as failure of lysosomal activity can lead to a multitude of diseases, including lysosomal storage disorders.

Plasma Membrane: The Cell’s Gatekeeper

The plasma membrane, a phospholipid bilayer embedded with proteins, defines the cell’s boundary and regulates the passage of substances into and out of the cell. Its selective permeability is fundamental to maintaining the internal environment, allowing essential nutrients to enter while blocking harmful substances. The dynamic nature of the membrane, characterized by fluid mosaic model properties, enables responsiveness to environmental changes and intercellular communication.

Chloroplasts: The Photosynthetic Engines

In plants and some protists, chloroplasts are organelles dedicated to photosynthesis, converting light energy into chemical energy in the form of glucose. Containing chlorophyll, these double-membrane-bound structures absorb sunlight and utilize it to power complex biochemical reactions, illustrating the extraordinary capacity of life forms to harness energy from their environment. This process underpins terrestrial food chains, supporting the vast array of organisms that rely on photosynthetic life for survival.

Conclusion: The Harmonious Interplay of Structure and Function

The cell, as a biological entity, exhibits a remarkable array of structures, each uniquely suited to perform specific functions critical to sustaining life. Understanding which cell structure is correctly paired with its primary function reveals insights not only into individual cellular activities but also into the broader tapestry of life. This knowledge invites a sense of awe, offering a glimpse into how mere microscopic structures orchestrate the symphony of biological processes that underpin existence. The intricate designs of cellular architecture exemplify the elegance of evolution, where form and function coalesce to create the diverse life forms encountered in nature. The study of cells is thus not merely an academic pursuit but a profound exploration of life’s wonders.