Geometry, a captivating branch of mathematics, often challenges individuals to conceptualize shapes and their relationships in a two-dimensional or three-dimensional space. One common task encountered in geometry is the identification of similar figures. These figures, despite potential differences in size, maintain proportional dimensions and congruent angles. Understanding the concept of similarity is fundamental not only in geometry but also in various applications ranging from art to architecture.

The question “Which choice is similar to the figure shown?” serves as an engaging entry point into the intricate world of geometric similarity. At first glance, this question may appear deceptively simple; however, it presents an array of underlying complexities that deserve exploration. As we embark on this analysis, consider the potential challenges that arise: What criteria must we satisfy to affirm that two figures are similar? How do we identify these criteria? Let us delve into the multifaceted nature of similarity in geometric figures.

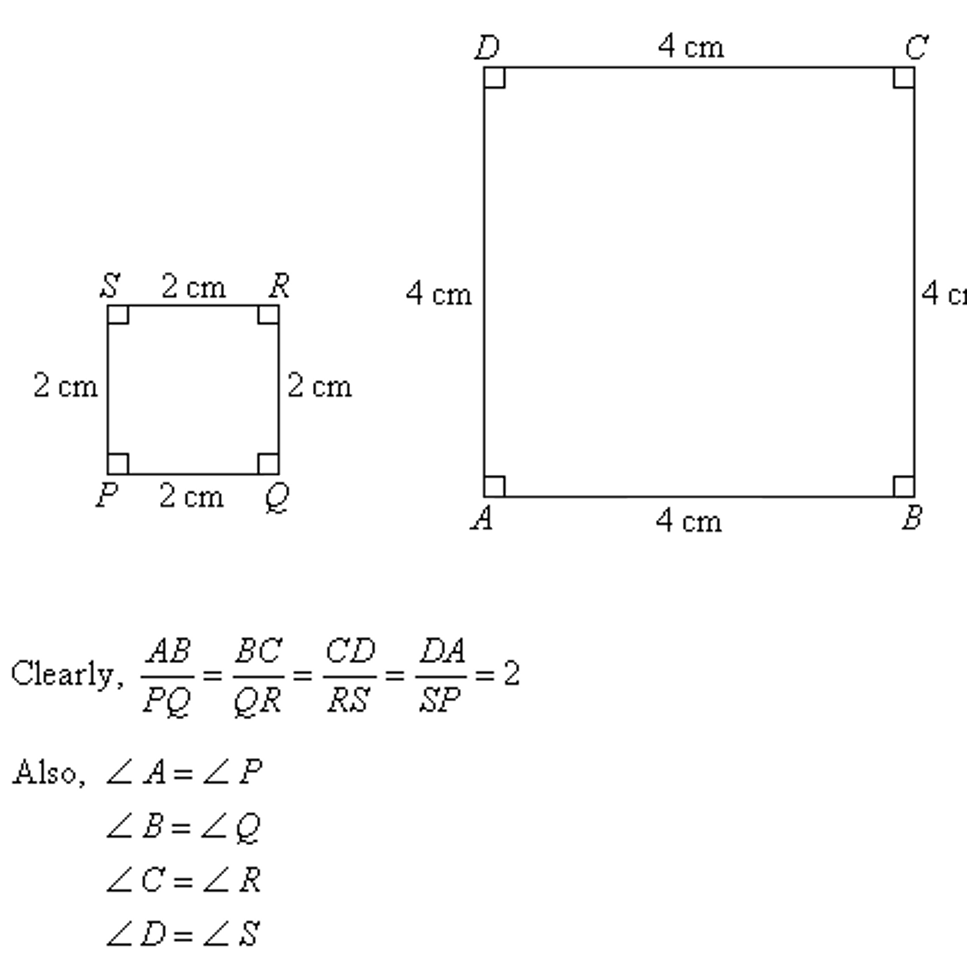

First and foremost, we must establish the essential criterion for similarity—proportionality. When examining two geometric figures, the ratio of corresponding side lengths is of paramount importance. For instance, if the lengths of two corresponding sides of one triangle measure 4 cm and 2 cm, while the corresponding sides of another triangle measure 8 cm and 4 cm, we find that these triangles are indeed similar. Such proportionality must hold for all corresponding pairs of sides, thus highlighting a fundamental rule: all pairs of corresponding sides must maintain uniform ratios.

In addition to side lengths, we must also consider the angles of the figures in question. Similar figures are characterized not only by proportionality but also by congruence of corresponding angles. This means that if two triangles are said to be similar, their interior angles must match precisely. For example, if Triangle A has angles measuring 30°, 60°, and 90°, then any triangle that is similar to Triangle A must also possess these exact angle measurements. This principle grants a robust framework for identifying similar figures: if two figures have proportional sides and equal corresponding angles, they are similar.

As we navigate this geometric terrain, the next cornerstone to address is the concept of scale factors. The scale factor is the ratio by which one figure is enlarged or reduced to produce another similar figure. In our previous example, the scale factor between the first triangle (with sides measuring 4 cm and 2 cm) and the second triangle (with sides measuring 8 cm and 4 cm) is 2. Recognizing scale factors aids significantly in validating the similarity—whether a figure has been scaled up or down does not affect its similarity, provided the proportions remain constant.

Moving beyond triangles, we arrive at the analysis of polygons. Here, the principles governing similarity remain steadfast. When examining polygons, one must ensure that corresponding sides are proportional and that corresponding angles are congruent. Moreover, a nuanced understanding emerges when we consider regular polygons, where not only dimensions but also shapes play a pivotal role. Regular polygons, such as squares and equilateral triangles, offer an intuitive grasp of similarity, as the uniformity of their structure dramatically illustrates the principle at hand.

In applying these principles, students and educators alike may encounter various strategies for determining similarity. A pragmatic approach involves the use of techniques such as the Side-Angle-Side (SAS) similarity theorem and the Angle-Angle (AA) similarity criterion. The SAS similarity theorem posits that if one side of a triangle is proportional to another side of a different triangle and the included angles are congruent, then the triangles are similar. Conversely, the AA similarity criterion asserts that if two angles of one triangle are congruent to two angles of another triangle, the triangles are similar, rendering the proportionality of the remaining side as a direct consequence.

As we ponder the question presented—“Which choice is similar to the figure shown?”—it is vital to approach the challenge methodically. One can initiate the process by systematically measuring the sides and angles of the given figure or using geometric tools such as protractors and rulers. Furthermore, visual aids, such as graphic representations or dynamic geometry software, can facilitate immediate comparisons, thereby streamlining the decision-making process.

Ultimately, recognizing similar figures is not merely an abstract mathematical task. It is an invitation to appreciate the inherent beauty of geometric relationships. Take a moment to consider practical applications; architects utilize the principles of similarity in scaling architectural designs for blueprints. Artists emulate proportions while creating life-like representations. By mastering the art of identifying similar figures, one not only hones mathematical skills but also unlocks a realm of creative potential.

In conclusion, mastering the identification of similar figures demands a robust understanding of proportionality, congruence, and scale factors. The challenge posed by the question “Which choice is similar to the figure shown?” encourages learners to engage critically with geometric relationships. It fosters an environment ripe for exploration, where individuals can challenge their perception of shapes and develop analytical skills that transcend the confines of mathematics. As one navigates through the world of geometry, embracing the complexities of similarity invites not only intellectual growth but an appreciation of the artistic and scientific marvels that geometry encompasses.