The exploration of biblical texts offers a myriad of revelations regarding the lives of the disciples who followed Jesus Christ. Among these figures, one stands distinctly apart due to his controversial actions and eventual betrayal: Judas Iscariot. This article delves into the complexities of Judas as a disciple, examining his role, motivations, and the resultant implications of his actions within the Christian narrative.

The character of Judas Iscariot occupies a unique position in the canon of the New Testament. Not only is he one of the twelve apostles, but he is also widely regarded as the archetype of treachery. To label him merely as a “criminal” ultimately simplifies a multifaceted persona steeped in intrigue, ambition, and despair. Understanding his motivations requires an examination of the socio-political context during which he lived, as well as the theological frames that shape his legacy.

Firstly, it is imperative to consider the socio-political backdrop of first-century Judea. At that time, the region was under Roman occupation, with widespread discontent amongst the Jewish populace. Many sought liberation from foreign rule, fostering a milieu rich with fervent zealotry and revolutionary sentiment. Judas Iscariot, as an ardently nationalistic figure—if some interpretations hold—may have envisioned his betrayal of Jesus as a means to incite a broader insurrection against the Romans. This potential motive of zealotry introduces complexity to his characterization as a mere sinner.

Judas’s actions, notably the betrayal of Jesus for “thirty pieces of silver,” have sparked extensive theological and ethical contemplation. In the Gospels, the amount is often depicted symbolically, suggesting a devaluation of loyalty in exchange for material gain. This transaction, shrouded in moral ambiguity, raises profound questions surrounding agency and predestination. Did Judas possess preordained malevolence, or was he ensnared by a series of decisions that ultimately culminated in his notorious act?

Moreover, the Gospels provide scant insight into Judas’s internal conflicts. Unlike Peter, whose denials are meticulously chronicled, Judas’s psychological landscape remains largely uncharted. This absence of narrative depth invites speculation regarding his motivations. Was he merely a greedy traitor, or an individual grappling with existential dilemmas? Such inquiries resonate within the broader themes of human nature, temptation, and redemption that permeate the New Testament.

The portrayal of Judas in various gospels further complicates our understanding. For instance, in the Gospel of Matthew, Judas’s remorse is palpable as he returns the silver coins, declaring, “I have sinned by betraying innocent blood.” His subsequent suicide signifies the intense weight of guilt and remorse, distinguishing him from other biblical figures who sought forgiveness through repentance. This act, culminating in his tragic death, leads to divergent interpretations: some view him as irredeemably lost, while others perceive a grim reminder of the fragility of human morality.

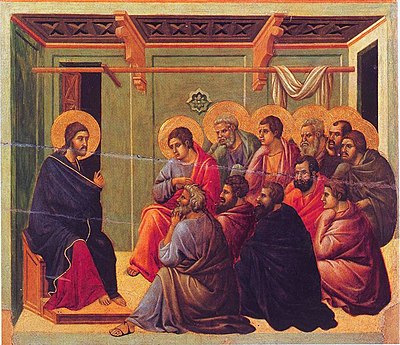

Interestingly, the Gospel of John presents an alternate perspective, suggesting a more sinister role for Judas as the “son of perdition.” His portrayal as being possessed by Satan during the Last Supper further cements the notion of his actions as preordained and malevolent. This narrative strain invites deeper philosophical ponderings about sin, free will, and divine foreknowledge. The theological implications are profound; if Judas’s betrayal was predestined, what does this mean for the concept of free will? Furthermore, can he be viewed as a necessary agent in the salvation narrative—or merely a villain in the grand tapestry of divine will?

In the realm of art and literature, Judas’s image has persisted as one of an arch-villain, but reinterpretations abound. Some modern portrayals endeavor to humanize him, suggesting that his actions sprung from desperation and disillusionment rather than pure malice. The pursuit of such perspectives highlights the enduring nature of his story, prompting audiences to confront their moral judgments and assumptions about betrayal.

Additionally, it is essential to consider the implications of Judas’s legacy on the Christian faith. Early Christian communities grappled with Judas’s treachery, and his character became a convenient vessel for discussions about the nature of sin and redemption. His name has become synonymous with betrayal; as such, it evokes a lexicon rife with moral condemnation. This portrayal can lead to societal stigma, wherein all individuals labeled “Judas” are perceived through a lens of unwavering disdain, thereby neglecting the potential for understanding and compassion.

Contemporary theological discussions regarding Judas remain vital, provoking reflection about the human condition. By engaging with his narrative, believers and scholars alike are challenged to confront their own imperfections and the complexities of divine grace. It beckons the question of whether redemption is attainable for those who falter, inviting a more nuanced conversation surrounding sin, guilt, and spiritual growth.

In summary, Judas Iscariot emerges as a profoundly complex figure molded by historical, psychological, and theological dimensions. While he is frequently denoted as a criminal for his betrayal, such a label fails to capture the intricacies of his motivations and the ensuing ramifications. Through an examination of his character, one can glean insights into broader themes of morality, agency, and redemption. The narrative of Judas Iscariot continues to resonate, urging an exploration of the human propensity for betrayal and the possibility of forgiveness—even for the most infamous among us.