Among the disciples of Jesus Christ, the figure that most poignantly embodies treachery and moral transgression is Judas Iscariot. Often described as a paragon of betrayal, his actions catalyzed not only the crucifixion of Jesus but also ensnared him in the narrative of spiritual perdition. Understanding the complexities of Judas’s character necessitates a thorough exploration of the scriptural accounts, historical interpretations, and theological ramifications surrounding his life and choices.

To embark on an examination of Judas Iscariot’s persona, one must first delineate the pivotal attributes assigned to him within the Gospel narratives. The synoptic Gospels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke—portray Judas primarily as the disciple who betrays his master for a paltry sum of thirty pieces of silver. This act of betrayal, while monumental in its consequences, elicits a plethora of interpretations, each unearthing layer upon layer of moral and spiritual implications.

In the Gospel of Matthew, Judas is depicted not merely as a financial traitor, but as a figure of profound remorse subsequent to the betrayal. His return of the silver pieces coupled with his hasty suicide underscores the profound psychological turmoil instigated by his actions. This narrative catalyzes a discourse surrounding the concepts of guilt and redemption, as it poses the question: can a transgressor ever hope for forgiveness after committing an act as egregious as betrayal?

The characterization of Judas extends beyond mere betrayal; he is often seen as a tragic figure. Renowned scholars have posited that his actions, while undeniably nefarious, were fueled by a complex interplay of predestination and free will. One such precept holds that Judas’s betrayal was foreordained, thereby infusing his actions with an element of fatalism regarding the divine plan for humanity’s salvation. The implications of this theological assertion compel readers to examine the delicate balance between divine sovereignty and human agency. Did Judas act freely, or was he merely a cog in the divine machinery?

Further examination reveals that Judas’s motivations may have been profoundly more intricate than mere greed. Some exegeses suggest that his actions may have been driven by a desire for political change, believing that Jesus’s radical message could incite a necessary uprising against Roman oppression. This perspective underscores the historical contextuality of Judean society during the First Century, replete with socio-political unrest. Such an interpretation invites discourse on how political fervor could intersect with spiritual existentialism, producing an outcome as tragic as betrayal.

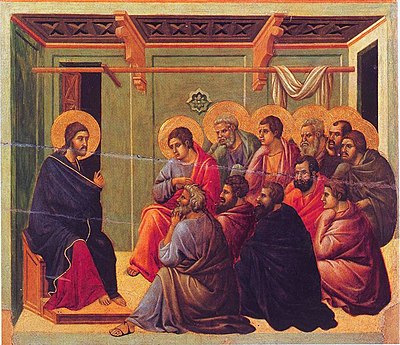

The persona of Judas Iscariot has proliferated various cultural representations. In artistic depictions throughout history, he has often been portrayed as a malevolent figure steeped in shadowy hues and depicted in a manner that accentuates his treachery. From medieval paintings to contemporary cinema, the archetype of Judas speaks to a broader archetype of “the betrayer.” His transgressions have offered fertile ground for literary explorations surrounding themes of betrayal, loyalty, and morality.

In examining the broader ramifications of Judas’s actions, one must delve into how his betrayal has historically shaped Christian thought. The theological discourse surrounding Judas is crucial, particularly in the context of soteriology— the study of salvation. His act can be interpreted as a necessary evil within the grand narrative of redemption; without his betrayal, the crucifixion, and consequently the resurrection, may never have occurred. Thus, Judas is ensconced within a paradox, as both villain and unwitting instrument of divine salvation.

The legacy of Judas Iscariot manifests not solely in the annals of theological discourse; it resonates within ethical discussions that permeate various disciplines. Psychologists and philosophers often reference Judas in conversations surrounding the nature of good and evil, exploring the capacity for individuals to commit heinous acts driven by situational pressures, psychological fragility, or ideological fervor. This reflects an enduring fascination with the dichotomies inherent in the human experience.

Moreover, the portrayal of Judas raises questions about accountability and culpability in moral decision-making. Can one be deemed wholly responsible for choices made under duress or as part of a perceived larger narrative? Such inquiries extend beyond the biblical narrative, echoing in contemporary ethical dilemmas faced by individuals in positions of power and influence.

Ultimately, the legacy of Judas Iscariot transcends the simplistic categorization of “murderer” or “traitor.” His story compels readers and scholars alike to wrestle with profound philosophical and theological questions about free will, redemption, and the nature of evil. The tragic figure of Judas is entrenched in the collective consciousness, serving as a cautionary tale of what it means to betray trust and the far-reaching consequences that ensue.

In conclusion, the character of Judas Iscariot epitomizes the complexities of morality and betrayal within the Christian narrative. His actions, steeped in historical, theological, and psychological nuance, continue to provoke rich discourse on the themes of guilt, redemption, and the duality of human nature. In recognizing the multifaceted nature of Judas—beyond the title of mere murderer—one engages with a narrative that interrogates the very essence of faith, loyalty, and the human condition.