When contemplating the enigmatic arena of gas behavior, one might liken it to a grand opera. Each gas, a performer on the stage, flaunts its unique characteristics, yet they are all subject to the same fundamental laws of physics. In this theatrical performance, understanding which gas sample possesses the greatest volume at standard temperature and pressure (STP) becomes pivotal for chemists, engineers, and the scientifically curious. This inquiry not only piques intellectual enthusiasm but also serves as a practical consideration in various applications. In this article, we embark on an empirical exploration of the variables at play in understanding gas volumes at STP.

To begin, it is crucial to elucidate the definition of standard temperature and pressure. STP is conventionally defined as a temperature of 0 degrees Celsius (273.15 Kelvin) and a pressure of 1 atmosphere (101.3 kPa). Under these conditions, one mole of an ideal gas occupies approximately 22.4 liters. Picture this volume as a majestic chamber, where the gas molecules dance in frenetic harmony. However, not all gases are created equal; their distinguishable qualities dictate how much space they occupy under STP conditions.

At the forefront of our inquiry lies the molar mass of gases. Molar mass plays a quintessential role in determining the volume gas occupies at STP. Heavier gases, akin to lumbering giants on stage, often yield a lesser volume than their lighter counterparts. Imagine, for instance, a gas with a molar mass of 40 g/mol compared to one with just 10 g/mol. The lighter gas, in this metaphorical opera, is likely to extend its reach, filling more volume despite having the same number of moles. The relationship between molar mass and molar volume reverberates through the world of gases, illustrating a profound principle of their behavior.

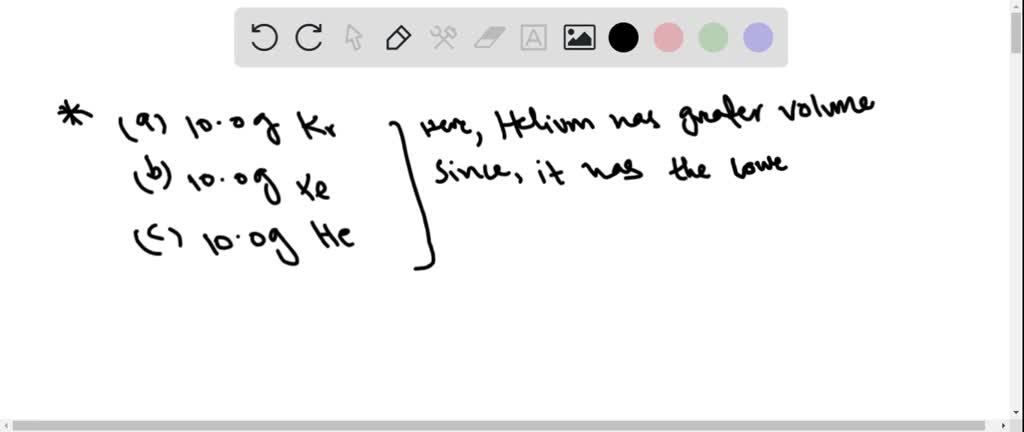

To ascertain which gas sample possesses the greatest volume at STP, we must traverse the realm of various gases. A classic example includes the charming noble gas, helium (He), with a molar mass of merely 4 g/mol. Its slender molecular stature allows it to occupy an impressive volume of 22.4 liters when measured at STP. When juxtaposed with gases like carbon dioxide (CO₂), which has a molar mass of approximately 44 g/mol, the disparity in volume becomes as stark as the dichotomy between a lightweight dancer and a hefty opera singer burdened by elaborate costumes.

Furthermore, the ideal gas law (PV = nRT) serves as the mathematical backdrop for our exploration. Here, P denotes pressure, V designates volume, n represents the number of moles of gas, R is the universal gas constant, and T signifies temperature. This equation, elegant in its simplicity, provides the framework through which we can comprehend gas behavior. By manipulating these variables, one can calculate and predict the behavior of various gases under standardized conditions, thereby enabling comparisons that reveal which gas dominates in volume.

As we delve deeper into specific examples of gas samples, the interplay of their molecular weights becomes even more pronounced. Let us consider a few representative gas samples:

- Helium (He): Molar mass of 4 g/mol, yielding a volume of 22.4 liters at STP.

- Oxygen (O₂): Molar mass of 32 g/mol, producing a similar volume of 22.4 liters for one mole.

- Carbon Dioxide (CO₂): With a greater molar mass of 44 g/mol, it occupies 22.4 liters like its lighter counterparts, yet does not change significance.

- Nitrogen (N₂): Molar mass of 28 g/mol, unfurling its presence with an identical volume of 22.4 liters at STP.

As one scans the ensemble, it becomes evident that the volume at STP does not discriminate based on gas species; rather, it standardizes the space in which each gas performs. However, we must remember, volume alone does not reflect the complexity of the gas’s behavior in various applications. The interplay of molar volume and molecular weight beckons for careful consideration, particularly in practical scenarios like balloon artistry, scuba diving, and cryogenic applications.

In applications such as respiratory environments, lighter gases like helium play a utility role, enabling divers to breathe more efficiently. In contrast, carbon dioxide serves as a critical component for plant life, yet its heavier molecular weight becomes a critical factor to ponder upon when assessing its volume in respiratory scenarios.

In conclusion, the query of which gas sample possesses the greatest volume at STP reveals a dynamic interplay of molar masses and the ideal gas law. Helium, with its dainty stature, often steals the limelight in volume considerations. Although each gas occupies the identical defined space of 22.4 liters at STP, the implicit qualities and practical implications of their densities demand consideration. This exploration highlights not just the scientific underpinnings of gas behavior, but the broader narrative of how these succinct pockets of matter influence our world beyond the confines of laboratory walls.

Understanding gas behavior invites us to appreciate the subtleties of nature which, much like a finely woven tapestry, composes the intricate fabric of our universe. As we continue our journey through the realms of chemistry and physics, the gas sample that possesses the greatest volume at STP shall remain a testament to the elegance and mystery of the natural world.